Important Note: Gary DeMar’s Facebook page has been taken down. To keep up with the latest from Gary and American Vision or to continue the conversation from articles, podcasts, or videos, please go to the AV Facebook page here.

Jason Bradfield responded to my article about mellō (“What Does Mellō Mean in Acts 24:15?”) which was a response to his article about mellō that was a response to a comment Kim Burgess made about the use of mellō in Acts 24:15 in The Hope of Israel and the Nations, Volumes One and Two. As expected, Bradfield dismissed my comments with an even more lengthy and meandering article. It’s a lot of words that miss the mark. My goal was not to prove full preterism or that mellō must be translated as “about to” in every case.

The Hope of Israel and the Nations

The reader and student of the Bible must first understand the content of the New Testament writings in terms of how those in the first century would have understood it. The New Testament is written against the background of the Old Testament. The shadows of the Old were fulfilled in the reality of the New. All the rituals and ceremonies were fulfilled in Jesus. The same is true of the temple, land, blood sacrifices, the nature of redemption, the resurrection of the dead, the breaking down of the dividing wall dividing Jews and Gentiles, and so much more. The New Testament's emphasis is on the finished work of Jesus and its application, not only to that Apostolic generation but to the world today.

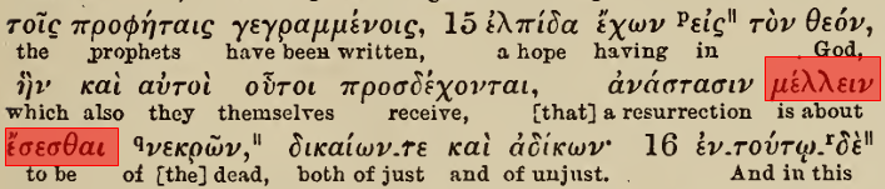

Buy NowMy purpose was to show that mellō can be translated as “about to” based on textual and contextual analysis with tools that are accessible to the average Christian. Bradfield appealed to lexicons. The lexicons will tell you that μέλλειν (mullein as used in Acts 24:15) is a verb form of μέλλω (mellō) which generally translates as “to be about to,” “to intend,” or “to be destined.” Check out these:

• F. Wilbur Gingrich, Shorter Lexicon of the Great New Testament: “μέλλω —1. be about to, be on the point of.”

• Sakae Kubo, A Beginner’s New Testament Grammar: “μέλλω I am about to.” No other definition is given.

• Bernard Brandon Scott, et al., Reading New Testament Greek: “μέλλω to be about to.” No other definition is given.

• Warren C. Trenchard, The Student’s Complete Vocabulary Guide to the Greek New Testament: “μέλλω I am about” is the first definition.

• J. Gresham Machen, New Testament Greek for Beginners: “μέλλω I am about” is the first definition.

Based on commentaries, selected lexicons, grammars, and parallel uses of μέλλω, “to be about to” is an acceptable translation. This conclusion should be the end of the debate. My response to Bradfield was not about the use of mellō generally but to its use in Acts 24:15 specifically. Mέλλω has been and can be translated as “to be about to.” How such a translation impacts the doctrine of the resurrection is another story.

I also showed that using some comments in articles by anti-full preterist Ken Gentry present a problem for critics of full preterism as it relates to Acts 24:15. If Daniel 12:2 is parallel to Acts 24:15, as many commentators argue, and Daniel 12:2 does not refer to “a future physical, general resurrection of the dead” (Question 2 in the Three Questions Letter), as Gentry argues, then Acts 24:15 can be interpreted in a way similar to how Gentry and others interpret Daniel 12:2.

Bradfield dismisses my use of Gentry because I don’t know his view. I don’t have to since Gentry signed the Three Questions Letter. Here’s what Bradfield wrote:

Gary doesn’t even know what I believe about Daniel 12. So whatever interpretive position Gentry holds there has no bearing on the case I’ve made. If Gary wants to debate Daniel 12 with Dr. Gentry, that’s fine—but it’s not the argument I’m making, and dragging it in only distracts from the real issue he has yet to address.

No, it is part of “the real issue” because the signers of the Three Questions Letter do not agree, a point I have repeatedly made. I suggest Bradfield and Gentry meet and get their stories straight because Gentry’s understanding of Daniel 12:2 affects “the real issue.”

Yes, I listed commentators and Greek-English interlinear translations. Bradfield seems to have a problem with this approach, but what I posted is factual. He wrote, “But listing commentators is not the same as making an argument. Simply quoting a series of sources who happen to favor the rendering ‘about to’ does not prove that such a translation is correct in Acts 24:15. It proves only that some commentators have chosen that gloss.” Here’s another commentator I found:

I (now) admit this to you that in accordance with the Way, which they call a sect, I serve (our) ancestral God and believe everything that is in accord with the law and that is written in the Prophets, and I have the same hope in God that these men themselves embrace, namely, that there will soon be a resurrection of both the righteous and the wicked (24:14-15)…. Paul claims that he serves the same ancestral God as do they and believes “everything that is in accord with the law and that is written in the Prophets” (24:14). Furthermore, returning to what Paul believes is at the heart of the dispute (cf. 23:6; 24:21), he shares with his accusers (Sadducees notwithstanding) “the same hope in God … that there will soon be a resurrection of both the righteous and the wicked” (24:15)…. Paul then makes explicit the true nature of the charge against him. His crime was in regard to this one thing that I shouted out when I stood among them: “I am being tried before you today concerning the resurrection of the dead!” (24:21; cf. 24:15)…. by speaking about righteousness, self-control, and the impending judgment (24:25a [Rom 2:1-11; 5:16; 11:33; 13:11-14]). … These specific terms also reflect important themes elsewhere in Acts. Christ is the “Righteous One” (cf. Acts 3:14; 7:52; 22:14), whose “impending judgment” of the living and the dead (Acts 10:42) will be administered with “righteousness/justice” (Acts 17:31).[1]

Listing commentators proves what I claim it proves. Some commentators translate mellō as “about to” and note that mellō is in the text, which some translations do not. Of course, if I had only listed commentators, Bradfield would have something of a case, but as anyone who reads my article can see, that was not my only argument.

It’s important to note that almost all Greek-English interlinear translations translate mellō as “about to.” Bradfield wrote:

[Greek-English interlinear translations] are mechanical tools, often produced with rigid one-to-one word glosses that do not always reflect contextually appropriate meanings. Just because some interlinears render mellō as “about to” does not make that the correct interpretation in Acts 24:15.

They may be “mechanical tools,” but they are tools as anyone who has debated a Jehovah’s Witness knows or has done any serious work on the Olivet Discourse dealing with Matthew 24:3 and 24:14. There are many Greek-English interlinears in book form (I have six different ones) and online. Should we ignore them? Not use them? Dismiss the Greek words that are used? Any seminary student studying Greek would have to acknowledge that mellō is present and do something with its translation. No student could ignore it. The student would have to make a translation decision since mellō is in the verse. Not translating it would be a major faux pas. “Definitely be”? “Should be? “Will be”? Shall be? Shall certainly be? “Will”? “Is to be”? These are translation options and so is “about to be” as lexicons, grammars, and commentaries show. Bradfield can dismiss “about to be,” but he can’t prove μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι cannot be translated as “about to be.” Often words are added to the Greek to smooth out its woodenness. A word-for-word translation can be awkward.[2] But there’s nothing awkward about translating mellō as “about to be” since that’s one of its lexical meanings, and it’s in the text. The prophecy wars extend far beyond dispensationalism.

Prophecy Wars: The Biblical Battle Over the End Times

There is a long history of skeptics turning to Bible prophecy to claim that Jesus was wrong about the timing of His coming at “the end of the age” (Matt. 24:3) and the signs associated with it. Noted atheist Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) is one of them and Bart Ehrman is a modern example. It’s obvious that neither Russell or Ehrman are aware of or are ignoring the mountain of scholarship that was available to them that showed that the prophecy given by Jesus was fulfilled in great detail just as He said it would be before the generation of His day passed away.

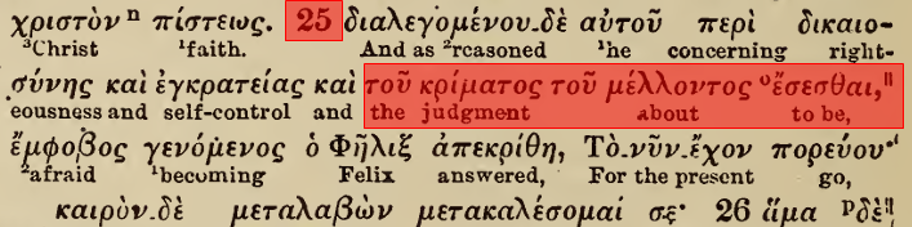

Buy NowIf a Greek student were to follow the lexicon in William Mounce’s Basics of Biblical Greek, he or she could translate mellō as “I am about to” since that’s the definition he gives. Mounce’s online dictionary of μέλλω has “to be about to, on the point of; to be destined, must; to intend to; (what is) to come, the future” for Acts 24:15. Not a single lexicon states that mellō can’t be translated as “about to” based on word usage. Paul brought up “the judgment that was about to [mellontos] come” in Acts 24:25. Similar language is used in 17:31 where mellō is found: “Because He has fixed a day in which He is about to [μέλλω] judge the world in righteousness…”). Sorry, but I’m going to quote from another commentary on Acts 24:25.

Paul no doubt complied with the request that he would state to them “the faith in Christ,” in doing which he could not fail to treat of Christian virtues and their corresponding vices, as the fruits of faith and unbelief respectively; and this plain statement, without digression or exaggeration, would suffice to reach the conscience and to rouse the apprehension of that coming judgment, literally, the judgment, that [is] about to be, the same verb that occurs above, in v. 15, and five times in the preceding chapter (23:3, 15, 20, 27, 30.)[3]

Bradfield cannot make the case that μέλλω can’t or shouldn’t be translated as “about to” in Acts 24:15. He and others can argue that it should be, but they cannot argue that it can’t be or shouldn’t be. Case closed. Again, this does not mean full preterism is true. Samuel Lee deals with the timing issue in his book Eschatology.

Eschatology

Predictions about the end have a long and less than accurate history. What’s the reason? How could so many be so wrong for so many years? Why does prophetic speculation run rampant today given the excesses of failed predictions based on the claimed certainties of “thus say the Scriptures”?

Buy NowTo summarize:

- Has Bradfield proved that mellō cannot be translated as “about to” in Acts 24:15? No.

- Does translating mellō as “about to” in Acts 24:15 mean that full preterism is correct? No.

- What is the best approach to determine the meaning of mellō in Acts 24:15? By locating other places where Luke uses the phrase μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι.

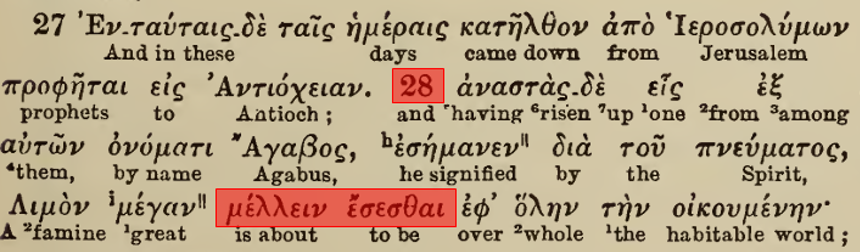

- Where does Luke also use μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι? Mέλλειν ἔσεσθαι is also used in Acts 11:28 and 27:10.

- Is it reasonable to assume that μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι should be translated as “about to” in 11:28? Yes. Mounce translates it as “about (mellein | μέλλειν | pres act inf) to take place” as do Greek-English interlinear translations.

- Is it reasonable to assume that μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι should be translated as “about to” in Acts 11:28 because a “great famine” did take place “over the oikoumenē,” that is, the world of their day (see Luke 2:1; Matt. 24:14), soon after Agabus prophesied. Yes.

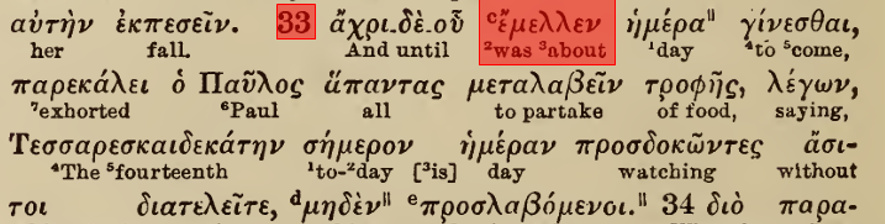

- Is it contextually reasonable to assume that μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι should be translated, “I perceive that the voyage is (mellein | μέλλειν | pres act inf ) about to take place” in Acts 27:10. Yes.

- What about Acts 27:33? Mounce translates ēmellen/ἤμελλεν ,“As day was about to dawn….”

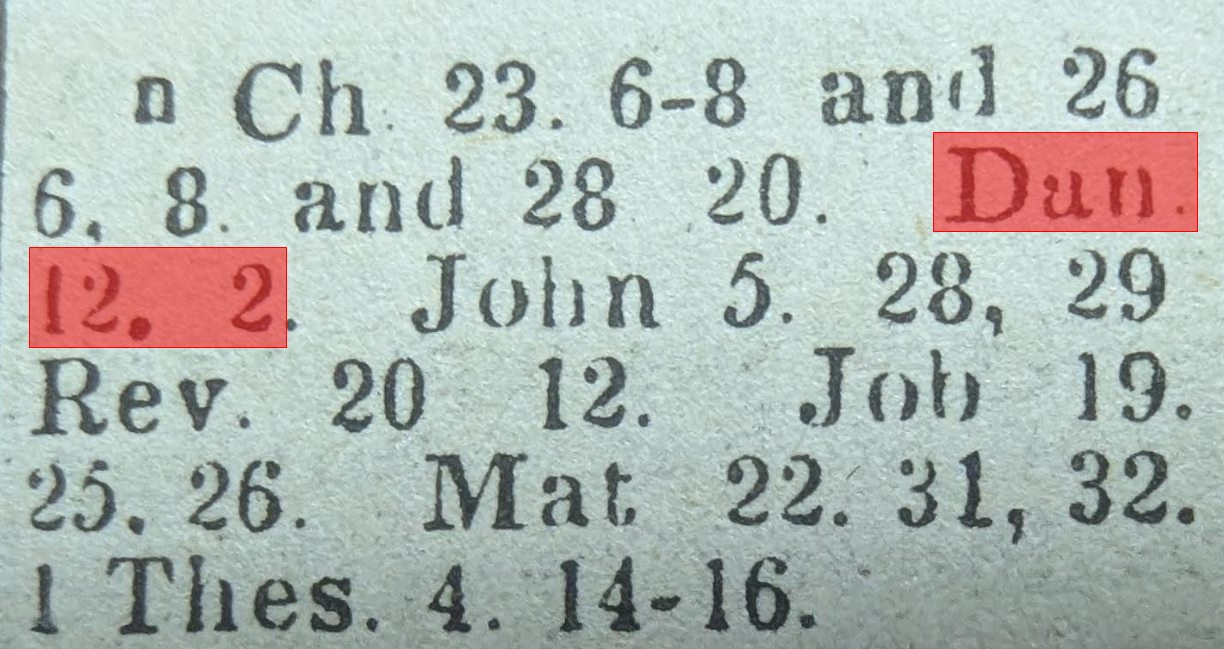

Jason Bradfield has not and cannot prove that μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι in Acts 24:15 cannot be translated as “is about to." Bradfield and Andrew Sandlin need to iron out their differences with Gentry on Daniel 12:2. Here’s an example of cross references related to Acts 24:15 from The New Self-Interpreting Bible. If Daniel 12:2 and Acts 24:15 describe the same event, and Gentry believes that Daniel 12:2 does not refer to physical bodies being raised from their graves at Jesus’ yet-to-be physical coming, how does he explain Acts 24:15? I can guess how he will try to reconcile the problem. Can you?

The signers of the Three Questions Letter need to get their stories straight, not based on the creeds or confessions, since none of them deal with the translation of mellō. Contrary to what Ken Gentry says, translating mellō as “about to” does not overturn 2000 years of history. Contrary to what Ken Gentry says, translating mellō as “about to” does not overturn 2000 years of history since there are other interpretive factors at play.

[1] Mikeal C. Parsons, Acts, Paideia Commentaries on The New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 327-329.

[2] William D. Mounce, Greek for the Rest of Us: Mastering Bible Study without Mastering Biblical Languages (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2003), 24-38.

[3] Joseph Addison Alexander, Acts of the Apostles Explained, 2 vols. (1862), 2:377

[4] “The phrase, holēn tēn oikoumenēn, is better translated ‘empire’ than ‘world,’ because ‘empire’ reflects Luke’s interest in the political nature of this term (see Luke 2:1; 4:5; Acts 17:6; 24:5; Johnson 1992, 206).” Mikeal C. Parsons, Acts, Paideia Commentaries on The New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 169.