Important Note: Gary DeMar’s Facebook page has been taken down. To keep up with the latest from Gary and American Vision or to continue the conversation from articles, podcasts, or videos, please go to the AV Facebook page here.

Jason Bradfield posted a lengthy article titled “Mellō and the Real Bias Problem” where he challenges the claim that the Greek word mellō always means “about to.” He states, “To begin, it’s critical to recognize that Greek lexicons are descriptive tools, not theological defenses. Lexicons such as BDAG,[1] LSJ,[2] and Thayer’s are designed to document how words were actually used in real-world texts, not to promote a specific doctrine.” Get your lexicons out and see if he’s right. You don’t have these lexicons? What did Bible readers do before these lexicons existed? Sorry, you’ll have to trust Jason Bradfield. If you’ve followed my work, it’s ultimately Scripture that determines how mellō is used. While Lexicons are helpful and useful, in the end comparing Scripture with Scripture is what counts since that’s what the early church had.[3]

Will any of what I’ve written here persuade Bradfield in the slightest? Don’t count on it because I’m not counting on it. I’ve written this article for students of the Bible who use the Bible as the Bible’s best interpreter.

Bradfield goes on to say, “The hyper-preterist claim that μέλλω always means ‘about to’ is linguistically and lexically indefensible.” There is no way anyone can demonstrate with certainty that mellō does not always mean “about to.” When a biblical writer uses mellō, as Luke does in his Gospel (12 times) and Acts (34 times), 46 out of 111 occurrences in the New Testament, we can (should) get a good idea of its meaning without going to Josephus and Diognetus as Gentry does. Why not list Bible commentators who translate mellō as “about to”? I have such a list that’s 230 pages of sourced direct quotations. The first time mellō is used in Acts, it’s translated as “about to” (3:3) by the NASB, but in Luke 3:7 it’s translated as just “coming.” The wrath wasn’t just coming; it was “about to come” as Luke 17:22-37, 19:41-44, and 21:1-36 (“all these things that are about to take place” [v. 36]) attest.

At no place can it be said that mellō can’t be translated as “about to” or its equivalent. The same is true for how mellō is used in Revelation. For example, mellō appears 13 times in Revelation, and Ken Gentry translates it as “about to” 12 times in his two-volume commentary on Revelation. His exception is with Revelation 1:19. Is there lexical certainty for not translating mellō as “about to” in 1:19? If there is, why do some commentators translate mellō as “about to,” and why did Gentry translate mellō in 1:19 as “about to” in the first edition of The Beast of Revelation and Before Jerusalem Fell? There is no certainty that mellō should not be translated as “about to” in 1:19. In fact, in the way mellō is consistently used in Revelation, five times in chapters 2 and 3, the burden of proof is on those who do not translate mellō as “about to” in 1:19. It’s easy to understand non-preterist interpreters not translating mellō as “about to” but not a preterist like Gentry who translates mellō as “about to” or its equivalent 12 times and translates it once as “will take place.”[4] Revelation was revealed to John in the mid-60s, and the events that follow took place before AD 70 as Gentry believes. This means, as Gentry used to teach, Revelation 1:19 should read, “Therefore write the things which you have seen, and the things which are, and the things which are about to take place [μέλλει γενέσθαι] after these things.” This reading makes perfect sense.[5]

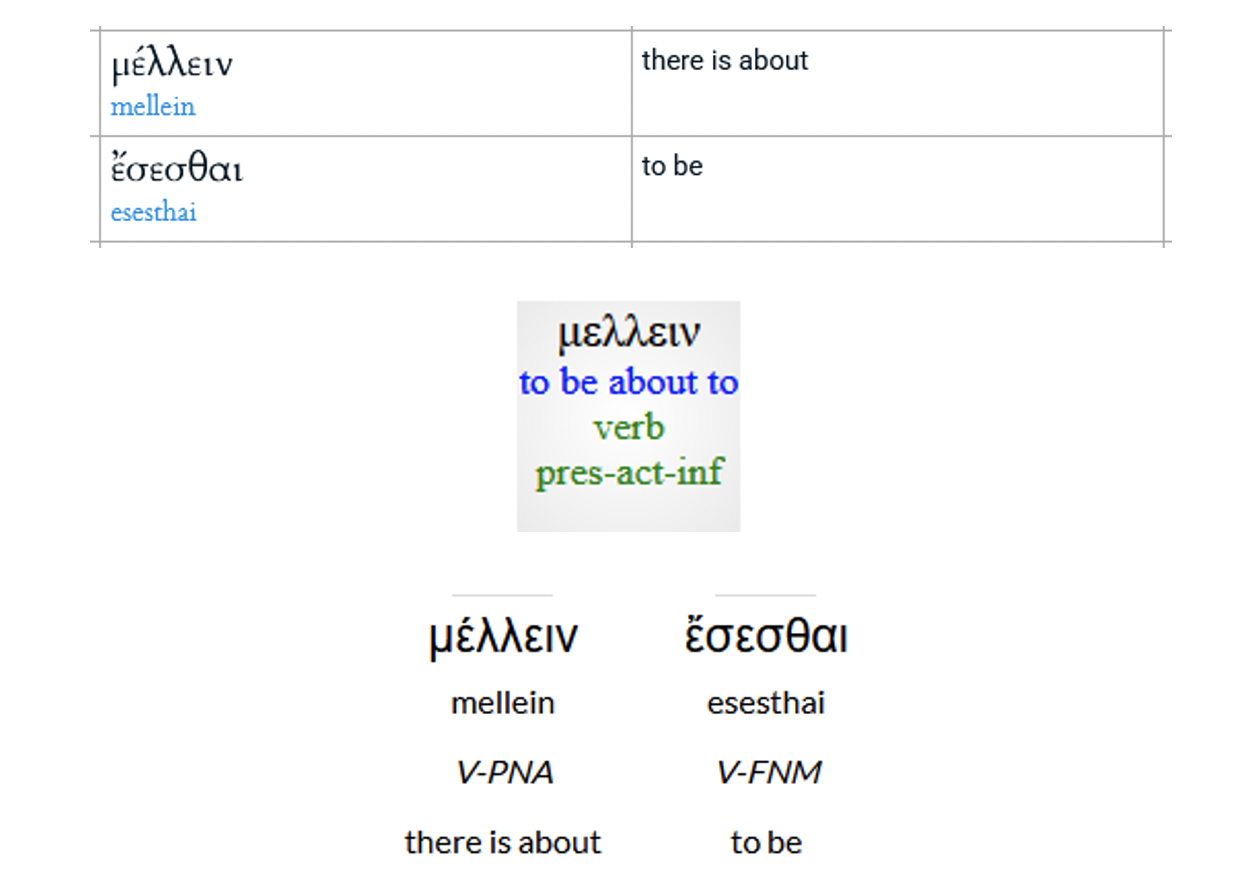

The only verse Bradfield mentions in his article is Acts 24:15: “having a hope in God, which they themselves also await, that there is about to be [μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι] a resurrection, both of the just and of the unjust.”[6] Bradfield writes, “The phrase μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι is a textbook case of μέλλω with the future infinitive—a construction that emphasizes future certainty, not imminent timing.” Let’s put his claim to the test. Let’s see his receipts and how well he shows his work.

Bradfield writes, “When we survey the [three] major lexicons, the evidence is consistent. [They categorize] μέλλω under multiple headings: to be about to, to be destined or certain, to delay, and to indicate future time…. All three lexicons treat μέλλω as a flexible, context-sensitive word—never a fixed technical term.” But seemingly not flexible enough to be translated as “about to” in Acts 24:15 and elsewhere. Lexicons are helpful, but let’s see how some commentators translate μέλλω” in Acts 24:15. They have access to the same lexicons and dictionaries that Bradfield and Gentry use.

• Philip W. Comfort, NTTTC, p. 424 — “there is about to be a resurrection.”

• Craig S. Keener, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary, 4:3403, note 449 — “Paul also apparently expects the judgment to happen soon (μέλλω need not mean this [see BDAG], but it is the most common sense in Luke-Acts), which might sound subversive to the Romans were it not for how widespread the view was in early Palestinian Judaism; surely Felix would know the difference between passive eschatological expectations and activist revolutionaries.”

• Samuel Lee, Eschatology, p. 160 — “‘Shall be a resurrection,’ ἀνάστασιν μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι. It may be worthy of notice in passing that μέλλειν implies that the Anastasis [resurrection] is that which is ‘about to be,’ and contradicts the common theory. Paul’s ‘hope’ was that the Anastasis was soon to be.… It should be remembered that the question of the day, as of any importance was, not one of the mode of existence in a future state, but the fact of such state.”

• A.J. Mattill, Jr. Luke and the Last Things, pp. 47-48 — “Resurrection before Long (Acts 24:15)… In 24:15 mellō appears with a future infinitive: mellein esesthai. Mellō with the infinitive expresses imminence. In classical Greek mellō was regularly used with the future infinitive, but only rarely so in Koine. Hence, Luke may be reverting to classical usage to give emphasis to his sense of urgency.… In view of these striking facts, Weymouth seems fully justified in rendering 24:15 as ‘before long there will be a resurrection both of the righteous and the unrighteous.’ To translate mellein esesthai here as a simple future would be to violate Luke’s own examples of what this phrase means and to ignore the extraordinary conjunction of mellō, imminence, and Paul.… To summarize our findings, mellein esesthai appears three times in Acts, and only there in the NT. Twice we learn from Luke himself precisely what he means, namely, very soon, speedily. Why, then, should not the third instance, 24:15, be so understood?” [See also Mattill under Acts 17:31.]

• Mikeal C. Parsons, PaCNT, Acts, p. 327 — “and I have the same hope in God that these men themselves embrace, namely, that there will soon be a resurrection of both the righteous and the wicked.”

• John B. Polhill, NAC, Acts, pp. 482-483, n.114 — “he shared the hope in the coming resurrection, the total resurrection of the wicked as well as the righteous. Paul’s words had a certain ominous tone. To mention the resurrection of the unjust could only imply one thing—the coming judgment.” … “If one follows Weymouth’s argument that μέλλω implies close proximity in time, then Paul’s reference to the resurrection in v. 15 is all the more urgent: ‘Before long there will be a resurrection.’”

• Robert Young, Literal Translation of the Bible — “having hope toward God, which they themselves also wait for, [that] there is about to be a rising again of the dead, both of righteous and unrighteous.”

• Robert Young, Critical Concise Comments on the Holy Bible — “15. ALLOW,] or ‘receive fully—(for) an understanding to be about to be of (the) dead, both of just and unjust.’”

Young's Concise Critical Commentary on the NT

Robert Young (1822-1888) published several editions of his Literal Translation of the Bible (YLT). He also published the Concise Critical Bible Commentary that was "Specially Designed for Those Teaching the Word of God." It’s his New Testament version of his Concise Critical Bible Commentary that American Vision is republishing. It’s an eye-opener when it comes to words often mistranslated and sometimes not translated in popular Bible translations, and you don’t need to know Greek to benefit from his commentary.

Buy NowGreek-English interlinear translations are a problem for Bradfield since most translate mellō as “about to.” The translators must do something with mellō since it’s in the Greek text. They can’t leave it untranslated like so many translations do.

Many of the commentaries I consulted do not mention mellō. Simon Kistemaker has this note on μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι in Acts 24:15: “the two infinitives both express the future and thus one is redundant. Consult the comment on 11:28.” (see below) But how far in the future? Timing is the issue, and μέλλειν is a present active infinitive, “to be about to.” The use of μέλλειν seems redundant if it does not mean “about to.” Why not just declare, “there will be a resurrection” if timing isn’t a factor?

If 11:28 is parallel to 24:15, and μέλλειν means “about to” in 11:28 in terms of its context, then why doesn’t it mean “about to” in 24:15? Consider these comments on 11:28:

• “One of these arose (ἀναστὰς), on a certain occasion, at a meeting held for public worship, and foretold, by the illumination of the Holy Ghost, that a severe famine would soon [mellō] afflict the whole known world [oikoumenē]” (Lange, Schaff, Gotthard, Gerok, and Schaeffer)

• “that a great famine was about to [mellō] be on the whole inhabited earth [oikoumenē]; which occurred under Claudius.” … “Luke states no details but only the message itself, that a great famine was impending, μέλλειν with the future infinitive pointing to a famine that is close at hand.” (Lenski)

• “μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι, that there was about to be) A double future.” (Bengel)

• “one of whom, named Agabus, being instructed by the Spirit, publicly predicted the speedy coming of a great famine throughout the world. (It came in the reign of Claudius.)” (Weymouth)

• “a great [= severe] famine was about to be over the whole inhabited earth…”[7]

• “was about to be contains a double future, as in 24:15; 27:10.”[8]

This recorded event is a fact of history “which came to pass in the days of Claudius Cæsar—Four famines occurred during his reign. This one in Judea and the adjacent countries took place, A.D. 41 [Josephus, Antiquities, 20.2.5]. An important date for tracing out the chronology of the Acts.”[9] The famine was about to happen, and it did. The use of mellō makes perfect sense.

This comment by Keener is interesting, “Some commentators have connected this prophecy with the image of an end-time famine common in apocalyptic texts; although that suggestion is possible, this prophecy was fulfilled in the reign of Claudius.” The use of μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι mitigates against an indeterminate future as the history of that time attests.

The Antioch Christians take this prophecy seriously and decide to send relief (probably in the form of money) to the believers in Judea, where the crop failures are known to be the most severe (11:29). Jerusalem has been looking after the young church spiritually (11:22-24), and now the daughter congregation sends material aid to the mother church. Paul later will urge this kind of mutual sharing to the benefit of both givers and receivers (2 Cor. 8:13-15; 9:11-14).[10]

It was the nearness of the famine that led the church to assist where it was needed. Not just a future famine but one that was near to them.

Gentry states, “The phrase [mellein esesthai] appearing in Acts 24:15 occurs only two other times in the New Testament (Acts 11:28 and 27:10). But it also appears in Josephus, and in a closely related construction in Diognetus.” Why go to secular sources when mellō is used 111 times in the New Testament? We need to know how Luke, who uses mellō more than any New Testament writer, uses mellō and mellein esesthai.

Gentry writes, “In Acts 27:10 Paul warns the captain of the ship he was on: ‘Men, I perceive that the voyage will certainly be [mellein esesthai] with damage and great loss.’ The pilot and the captain of the ship disagreed and forged ahead. Paul was prophesying the ship’s wrecking as a certain event.” It was a certain event that was “about to” happen. Luke defines mellō for us in verse 14: “But before very long….” The storm was about to destroy the ship and the lives of Paul, the passengers, and the crew, unless they acted on Paul’s instructions. The looming calamity is crucial in terms of their actions. A delay would mean their deaths.

Here are Gentry’s comments on Acts 11:28 where mellein esesthai is also used.

In Acts 11:28 Agabus prophesies “that there would certainly be [mellein esesthai] a great famine all over the world.” And we read that it most certainly did come to pass in the reign of Claudius.

Exactly! There wasn’t a delay of nearly two millennia as Keener mentioned is “common in apocalyptic texts.” What Gentry claims to disprove, he proves. Mellein esesthai should be translated “about to” because the famine was “about to” happen to those living then, and it did.

Prophecy Wars

There is a long history of skeptics turning to Bible prophecy to claim that Jesus was wrong about the timing of His coming at “the end of the age” (Matt. 24:3) and the signs associated with it. Noted atheist Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) is one of them and Bart Ehrman is a modern example. It’s obvious that neither Russell or Ehrman are aware of or are ignoring the mountain of scholarship that was available to them that showed that the prophecy given by Jesus was fulfilled in great detail just as He said it would be before the generation of His day passed away.

Buy NowSome commentators link Acts 24:15 to Daniel 12:2. For example, “‘A resurrection of both righteous and unrighteous people’ reflects Daniel 12:2….”[11] I would also include Matthew 16:27. (The Bible speaks elsewhere of God raising all people to face judgment (e.g., Matt. 25:31-33; 25:46; John 5:28-29; Acts 10:42; Acts 17:31; Rev. 20:12-15). See my book Prophecy Wars for a discussion of the meaning of Matthew 16:27 that also uses mellō about Jesus coming to “recompense every man according to his deeds.” If Acts 24:15 is similar to Daniel 12:2, as many commentators claim, then Gentry’s comments on Daniel 12:2 are a problem for Bradfield and the following from Gentry.

Daniel appears to be presenting Israel as a grave site under God’s curse: Israel as a corporate body is in the “dust” (Da 12:2; cp. Ge 3:14, 19). In this he follows Ezekiel’s pattern in his vision of the dry bones, which represent Israel’s “death” in the Babylonian dispersion (Eze 37). In Daniel’s prophecy many will awaken, as it were, during the great tribulation to suffer the full fury of the divine wrath, while others will enjoy God’s grace in receiving everlasting life. Luke presents similar imagery in Luke 2:34 in a prophecy about the results of Jesus’s birth for Israel: “And Simeon blessed them, and said to Mary His mother, ‘Behold, this Child is appointed for the fall and rise of many in Israel, and for a sign to be opposed.’”

*****

Daniel only picks up on resurrection imagery and, like Ezekiel, applies that to corporate Israel. He is teaching that in the events of AD 70, the true Israel will arise from old Israel’s carcass, as in a resurrection.

Gentry does not interpret Daniel 12:2 as the “eschatological, consummate resurrection,” that is, dead bodies being raised. In an endnote to his article “Resurrection in Daniel 12:2” he writes, “Thus, Da 12 does not directly teach individual, bodily resurrection. Nevertheless, the fact that it uses such language shows that a literal bodily resurrection lies behind the image, and so it indirectly affirms the future bodily resurrection.” Gentry does this a lot. “‘Daniel 12 does not teach individual bodily resurrection,’ but there is still a future bodily resurrection.” He does this with Revelation 1:7 after spending more than 20 pages explaining that this verse was fulfilled a few years after it was revealed to John.

[1] Walter Bauer, Frederick W. Danker, William F. Arndt, F. Wilbur Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature.

[2] Liddell-Scott-Jones.

[3] Another approach is to “examine its uses in Classical and Hellenistic Greek, and (iii) compare Septuagint usage with that of Classical and Hellenistic Greek.” Anssi Voutila, “ΜÉΛΛΩ-Auxiliary Verb Construction in the Septuagint,” In the Footsteps of Sherlock Holmes: Studies in the Biblical Text in Honour of Anneli Aejmelaeus (214), 195. If this is what Christians need to have at their disposal, then “reading the Scriptures daily” (Acts 17:11) to see if anything is so is an exercise in futility.

[4] Gentry, The Divorce of Israel, 1:351. “When Jesus speaks of ‘the things which will take place after these things,’ he uses the verb mellō, which can mean ‘about to,’ in the sense of nearness in time…. Though John’s basic concern in Revelation is with the near term …, we probably should not translate the word mellō as emphasizing nearness, since it seems intentionally to be avoiding the clearer language already appearing in the context (1:1, 3).” It seems to me that using mellō supports what 1:1, 3; 22:6, 10 state and its 12 other uses in Revelation.

[5] Literal Standard Version

Write the things that you have seen, and the things that are, and the things that are about to come after these things;

Berean Literal Bible

Therefore write the things that you have seen, and the things that are, and the things that are about to take place after these,

Young’s Literal Translation

‘Write the things that thou hast seen, and the things that are, and the things that are about to come after these things;’

Smith’s Literal Translation

Write the things thou hast seen, and which are, and which are about to be after these things;

Literal Emphasis Translation

Write then the things that you have seen, and the things that are, and the things that are about to happen after these.

Godbey New Testament

Therefore write the things which you have seen, and the things which are, and the things which are about to take place after these;

Weymouth New Testament

Write down therefore the things you have just seen, and those which are now taking place, and those which are soon to follow:

[6] ἐλπίδα ἔχων εἰς τὸν Θεόν, ἣν καὶ αὐτοὶ οὗτοι προσδέχονται, ἀνάστασιν μέλλειν ἔσεσθαι δικαίων τε καὶ ἀδίκων

[7] Robert H. Gundry, Commentary on the New Testament: Verse-by-Verse Explanations with Literal Translation (2010), 557.

[8] Horatio B. Hackett, “A Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles,” An American Commentary on the New Testament (1882), 4:141

[9] Jamieson-Fausset-Brown Bible Commentary on Acts 11:28.

[10] Chalmer Ernest Faw, Acts, Believers Church Bible Commentary (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1993), 133.

[11] Gundry, Commentary on the New Testament, 557.