My wife and I were watching Season 3, Episode 4 “A Little Drop of Poison” from the British version of Professor T when the Professor mentioned Lillian Gilbreth and her book The Psychology of Management (1914) regarding “time and motion studies.” The study triggered something for the Professor that was a clue to help him solve a crime. The current condition of our mismanaged government might be able to glean some pointers from Gilbreth studies given the subtitle: The Function of the Mind in Determining, Teaching, and Installing Methods of Least Waste.

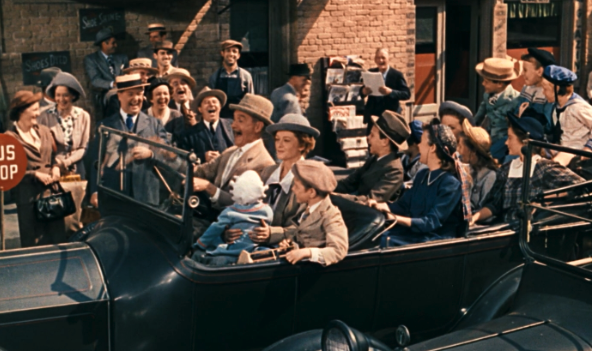

For me, the Professor’s comment reminded me of the 1950 film Cheaper by the Dozen. The setting for the movie, based on a 1946 novel of the same name written by Frank Gilbreth, Jr. and Ernestine Gilbreth Carey,[1] two of the dozen children the Gilbreths had, is New Jersey. The movie and novel tell the story of time and motion study and efficiency experts Frank and Lillian Gilbreth and their twelve children. It’s unfortunate that this family-friendly movie has been eclipsed by the crude remake starring Steve Martin and Bonnie Hunt. There is no comparison with the original. Avoid the remake and its sequel.

Using Classic Films to Teach the Christian Worldview

In this talk, Gary DeMar makes the point that classic movies are excellent teaching tools for a Christian worldview—for children and adults. Classic movies are often heavily dialogue-based, which provides a necessary counterpoint to the visually stimulating and soundbite-driven modern method of moviemaking. Real life is about real conversations, and classic movies provide a great virtual training ground for thinking and living in the real world of ideas and consequences. Also includes illustrated PDF ebook that helps to reinforce and explain the concepts discussed in the lecture, as well as Gary's 89-page movie recommendation list.

Buy NowFrank Gilbreth (1868-1924) started his work career as a bricklayer and then advanced to contractor. It’s the contractor’s job to get efficient work out of his laborers while retaining quality. He noticed that his bricklayers were inefficient. From his observations, he developed a more efficient way to lay bricks. His recommendations were initially opposed by the unions because it meant fewer workers were needed for a job. Along with his wife Lillian (1878-1972), the Gilbreths made a career and science of studying the way people work. The invention of the motion picture camera assisted them in breaking down movements into fractions of time to observe the smallest motions in workers.

They originated micro-motion study, a breakdown of work into fundamental elements now called therbligs (derived from Gilbreth spelled backwards [with the t and h transposed]). These elements were studied by means of a motion-picture camera and a timing device which indicated the time intervals on the film as it was exposed.[2]

Repeated movements done the wrong way would result in fatigue and injury. They emphasized that there was only the “one best way” to perform a task.

The Gilbreth’s were more than theorists. They put their observations into action in the real world. Frank Gilbreth was the first to propose that a surgical nurse serve as an assistant or “caddy” to a surgeon. A well-trained surgical nurse now hands surgical instruments to the surgeon as he calls for them. Armies teach recruits how to disassemble and reassemble their weapons while blindfolded based on studies and recommendations made by the Gilbreths. This ability undoubtedly has saved countless lives as soldiers learned how to clean and repair their machine guns day or night.

Frank Gilbreth used every opportunity to study motion and improve the way people work. When his children came down with tonsillitis, he insisted that the operations be done in his own home so he could film the procedure.

There’s one delightful scene in the film that shows the change in social and moral attitudes from the 1930s. Mildred Natwick’s [3] character visits the Gilbreth household representing a Planned Parenthood-like organization. Mrs. Gilbreth is amused by the visit and calls her husband. Showing indignation, as only Clifton Webb can, he signals for the children to assemble in the living room. They come running from every corner of the house. The woman is shocked and bolts for the door muttering as she goes that someone was pulling her leg for recommending that she ask if Mrs. Gilbreth would like to join the anti-child and pro-abortion organization.

A second book, Belles on Their Toes, published in 1952, continues the family’s adventures after the unexpected death of Mr. Gilbreth in 1924. Belles on Their Toes was also made into a film, starring Jeanne Crain and Myrna Loy (1952) and focused on the lives of Mrs. Gilbreth and her children. Lillian Gilbreth took over her husband’s work and advanced his recommendations and became a well-respected advocate for the scientific study of motion in her own right. She graduated from the University of California with a B.A. and M.A. and went on to earn a Ph.D. from Brown University. Like her husband, she lectured at Purdue University.

This is a wonderful film that shows how loving parents juggle raising children, education, and work without losing the focus on any of them.

Trivia

On the shelf in the living room is a picture of the real-life Frank Gilbreth in uniform as an Army Major during WWI. This is visible outside the makeshift operating room during the mass tonsillectomies.

Frank Gilbreth helped to train a fast typist to help the Remington Company win a world-wide typing competition. He trained the typist to focus on the copy he was typing, not the keys.

Among other things, Lillian Gilbreth patented an electric food mixer and a trash can with a step-on lid opener.

Frank Gilbreth, Jr. (1911-2001) wrote under the pen name Ashley Cooper for the Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina and compiled the Dictionary of Charlestonese, a pamphlet that poked fun at the Charleston accent.

For the creationist crowd:

Man on the street: “Hey Noah, what are you doing with that Ark?”

Frank Gilbreth: “Collecting animals like the good Lord told me brother. All we need now is a jackass. Hop in!”

Points to Ponder

Question: In what ways has the world changed for the average household when compared to the way life is portrayed in Cheaper by the Dozen?

Answer: There are obvious observational changes like hair styles, dress, and social attitudes. Consider what it would take to take care of a family of 14 in terms of washing clothes, shopping for food, and transportation. There were no large grocery stores for one-stop shopping. Fruits and vegetables were often sold by farmers who brought their produce to the city. Butcher shops were common. Most women baked their own bread and made their own pasta and pies. Hot water heaters were often a luxury. Water was heated on top of the stove, and many stoves were wood burning. Clothes were often handmade and passed down. Washing machines were a luxury, and even these were primitive. Clothes were placed in a tub of water and soap, rinsed, and then hand-cranked through a ringer to squeeze out the water. They were then hung outside on lines to get them dry.

Most women were up at dawn to begin their day of work and still working after their children were in bed. There were no dishwashers, electric appliances, garbage disposals, microwave ovens, or air conditioning.

The mass production of the antibiotic Penicillin was not readily available until the early 1940s. There was no television and no conception of the internet or email. There was almost no “Public Assistance,” that is, government welfare programs.

MPAA Rating: Not rated

Running Time: 85 minutes

Cast

Clifton Webb: Frank Bunker Gilbreth

Myrna Loy: Lillian Gilbreth

Jeanne Crain: Ann Gilbreth

Edgar Buchanan: Dr. Burton

Barbara Bates: Ernestine Gilbreth

Mildred Natwick: Mrs. Mebane

[1] There is an extended bibliography on the Gilbreths at http://gilbrethnetwork.tripod.com/gbooks.html

[2] http://gilbrethnetwork.tripod.com/bio.html

[3] Natwick is remembered for small but memorable roles in several John Ford film classics, including 3 Godfathers (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and The Quiet Man (1952). She played Miss Ivy Gravely, in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Trouble with Harry (1955), and a sorceress in The Court Jester (1956). She received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress for her performance as Edith Banks in the 1967 film Barefoot in the Park.