I was raised in the Roman Catholic Church. My Catholic upbringing included Catholic school through the fifth grade and serving as an altar boy through my teen years. My first dose of a foreign language was Latin, a prerequisite if you were an altar boy in the 1950s and 1960s.

After becoming a Christian in 1973, I began to question several Catholic doctrines based on the Bible. It was sola scriptura—Scripture alone—not the Bible plus anything else that led me to reconsider what I had been taught as a child about Catholicism. Those doctrines that lined up with the Bible, I retained. Those doctrines that could not be supported by an appeal to the Bible, I rejected. Again, sola scriptura was the reference point.

The doctrine of sola scriptura has been questioned by several former Protestants who have embraced the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. Once the doctrine of sola scriptura is rejected a Pandora’s Box of doctrinal additions is opened. As one Catholic writer asserts, “Scripture has been and remains our primary, although not exclusive, source for Catholic doctrines.”[1] This is the nature of the dispute. While Protestants believe Scripture is the “exclusive” source for doctrine and life the Catholic Church asserts that extra-biblical tradition plays an almost equal role.

1599 Geneva Bible

Tyrants have always feared God’s Word, especially when it is translated so the average person can read, understand, and apply it to every area of life. What was true then is no less true today. Having your own copy of the Geneva Bible will connect you to a time when many faithful and brave Christians understood what it meant to stand and act on the Word of God no matter the cost. This completely re-typeset edition of the 1599 Geneva Bible commemorates this history.

Buy NowA book written by former Protestants Scott and Kimberly Hahn got some attention when it was first published. The Hahns have become effective apologists for the Catholic position. Scott, a former Presbyterian minister, and his wife, consider their embrace of Catholicism as a homecoming. In fact, the title of their book is Rome Sweet Home: Our Journey to Catholicism.[2] While there is much that I would like to deal with in their book, my goal is to concentrate on the center—the doctrine of sola scriptura.

After reading Rome Sweet Home, I came away bewildered. I could not believe how poorly the Hahns argued for Catholic dogma. For example, Kimberly tells the story of how she had questioned saying the Rosary, a belabored recitation of the “Hail Mary” and other prayers. She had always thought that the practice was “vain repetition” (Matt. 6:7). After some instruction by a nun, Kimberly saw the error of her ways. The nun told Kimberly that we are like children when we pray. I might tolerate my child saying the same thing over and over again when he was first learning to talk, but not for long.

The Bible tells us that we are to “grow in respect to salvation” (1 Peter 2:2; also Eph. 4:15). Consider the passages that speak about maturity:

• “For everyone who partakes only of milk is not accustomed to the word of righteousness, for he is a babe. But solid food is for the mature, who because of practice have their senses trained to discern good and evil” (Heb. 5:13-14).

• “Therefore, leaving the elementary teaching about the Christ, let us press on to maturity, not laying again a foundation of repentance from dead works and of faith toward God” (Heb. 6:1).

• “When I was a child, I used to speak as a child, think as a child, reason as a child; when I became a man, I did away with childish things” (1 Cor. 13:11).

While we are God’s children, we are not encouraged to act childish. Anyway, why pray the “Hail Mary,” with its non-biblical and unbiblical line of “Holy Mary Mother of God pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death”?[3] I mean, if you’re going to say a prayer repeatedly, why not use the one Jesus taught His disciples to pray? Why not the Lord’s Prayer? When Jesus’ disciples asked Him to teach them to pray, He didn’t teach them the “Hail, Mary.”

No biblical justification can be found for praying the Rosary. But this does not matter to Catholics since they have tradition on their side. The real debate, however, is whether sola scriptura is a doctrine that is taught in the Bible. Does the Bible teach that the Bible alone is the Christian’s “only rule of faith and obedience”?

One of the things that sent Scott Hahn over the edge into considering Roman Catholic doctrine was a question a student asked him about sola scriptura. Here is how Scott recounts the confrontation:

“Professor Hahn, you’ve shown us that sola fide isn’t scriptural—how the battle cry of the Reformation is off-base when it comes to interpreting Paul. As you know, the other battle cry of the Reformation was sola scriptura: the Bible alone is our authority, rather than the Pope, Church councils or Tradition. Professor, where does the Bible teach that ‘Scripture alone’ is our sole authority?”[4]

What was Scott’s response? “I looked at him and broke into a cold sweat.” He writes that he “never heard that question before.” This encounter shook Scott. He writes that he “studied all week long” and “got nowhere.” Then he “called two of the best theologians in America as well as some of [his] former professors.”[5] I admit that if I got the answers that Scott received from these unnamed “two best theologians in the country” I also would give up the doctrine of sola scriptura.

What amazes me is that a seminary-trained scholar like Scott Hahn had to make these calls. Demonstrating sola scriptura from the Bible is not very difficult. Jesus used the Bible to counter the arguments of Satan. Scripture was quoted, not extra-biblical tradition (Matt. 4:1-10 and Luke 4:1-12). The same can be said with His debates with the religious leaders. He asked them, “Did you never read in the Scriptures?” (Matt. 21:42). Appeal is not made to any ecclesiastical body, the priesthood, or tradition (Mark 7:1-13).

The Sadducees, who say there is no resurrection, hoped to trap Jesus with a question that seems to have no rational or biblical answer. Jesus, with all the prerogatives of divinity, could have manufactured a legitimate and satisfactory answer without an appeal to Scripture. He did not. Instead, he tells them, “You are mistaken, not understanding the Scriptures, or the power of God” (Matt. 22:29). Here we find Jesus rejecting ecclesiastical opinion—as represented by the Sadducees—in favor of sola scriptura.

To whom does Abraham appeal in the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus? Does he point to tradition? He does not. Ecclesiastical authority? No. A saint? (Abraham himself would have qualified.) No. Abraham answers, “They have Moses and the Prophets; let them hear them” (Luke 16:29). The rich man is not satisfied with this response. “No, Father Abraham, but if someone goes to them from the dead, they will repent!” (16:30). A miracle will surely convince my brothers! Abraham’s appeal, however, is to Scripture: “But he said to him, ‘If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded if someone rises from the dead’” (16:31).

On the road to Emmaus Jesus presents an argument to explain His death and resurrection: “And beginning with Moses and with all the prophets, He explained to them the things concerning Himself in all the Scriptures” (Luke 24:27). No mention is made of tradition. If you want eternal life, what are you to search for? The Bible says, “You search the Scriptures, because you think that in them you have eternal life; and it is these that bear witness of Me” (John 5:39).

The Pharisees, who were notorious for distorting the Word of God by means of their “tradition” (Mark 7:8), still could speak the truth if they stuck with sola scriptura. When the “scribes and the Pharisees” seat “themselves in the chair of Moses,” that is, when they are faithful in their use of Scripture, “do and observe” what they tell you (Matt. 23:2-3). When Paul “reasoned” with the Jews, what revelational standard did He use? “And according to Paul’s custom” he “reasoned with them from the Scriptures” (Acts 17:2). Paul, who claimed apostolic authority (Rom. 1:1; 11:13; 1 Cor. 9:1; Gal. 1:1), did not rebuke the Berean Christians when they examined “the Scriptures daily, to see whether these things” he was telling them were so (Acts 17:11). Notice that the Bereans were equal to Paul when it came to evaluating doctrine by means of Scripture.

Paul continually argued in terms of sola scriptura: “For what does the Scripture say?” (Rom. 4:2). Roman Catholic doctrine would add, “and Church tradition as expressed in the magisterium.” Paul “opposed” Peter, the supposed first Pope, “to his face” over a doctrinal issue (Gal. 2:11), demonstrating that “a man is not justified by the works of the Law but through faith in Christ Jesus” (2:16).

When church leaders met in Jerusalem to discuss theological matters, again, their appeal was to Scripture. Their deliberations had to “agree” with “the words of the Prophets” (Acts 15:15). The book of Acts is filled with an appeal to sola scriptura: the appointment of a successor to Judas (1:20); an explanation of the signs at Pentecost (2:14-21); the proof of the resurrection of Jesus (2:30-36); the explanation for Jesus’ sufferings (3:18); the defense of Stephen (7); Philip’s encounter with the Ethiopian and the explanation of the suffering Redeemer (8:32-35): “Philip opened his mouth, and beginning with this Scripture [Isa. 53] he preached Jesus to him” (Acts 8:35). In the book of Acts the appeal is always to Scripture (10:43; 13:27; 18:4-5; 24:14; 26:22-23, 27; 28:23). There was no appeal to an extra-biblical tradition.

But what of those verses that discuss the validity of tradition? These were troubling to the Hahns, especially 2 Thessalonians 2:15: “So then, brethren, stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught, whether by word of mouth or by letter from us.” No church council was called to place its imprimatur on these Old Testament books. The Old Testament canon—Scripture—was not the product of the Old Testament church. “The church has no authority to control, create, or define the Word of God. Rather, the canon controls, creates and defines the church of Christ.”[6]

Once the completed written revelation was in the hands of the people, appeal was always made to this body of material as Scripture. Scripture plus tradition is not a consideration. In fact, Jesus condemns the Pharisees and scribes because they made the claim that their religious traditions were on an equal par with Scripture (Mark 7:1-13). The Roman Catholic answer to this is self-refuting: “Jesus did not condemn all traditions; he condemned only erroneous traditions, whether doctrines or practices, that undercut Christian truths.”[7] Precisely. How does one determine whether a tradition is an “erroneous tradition”? Sola scriptura! The Catholic Church maintains that the appeal must be made to the Church whose authority is based on Scripture plus its own traditions. But this is begging the question. How could anyone ever claim that a tradition is erroneous if the Catholic Church begins with the premise that Scripture and tradition, as determined by the Catholic Church, are authoritative? Who’s interpreting the interpreters?

But doesn’t the New Testament justify the use of tradition (2 Thess. 2:15; 3:6)? New Testament tradition is the oral teachings of Jesus passed down to the apostles and special revelation given to the New Testament writers. This is why Paul could write:

Now I make known to you, brethren, the gospel which I preached to you, which also you received, in which also you stand, by which also you are saved, if you hold fast the word which I preached to you, unless you believed in vain. For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, and that He was buried, and that He was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures (1 Cor. 15:1-4).

When the Old Testament canon closed, that canon was referred to as Scripture (2 Tim. 3:16-17). The same is true of the development of the New Testament canon. After a complete end had been made of the Old Covenant order in AD 70, the canon closed. All New Testament books were written prior to the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70.[8] All that God wanted His church to know about “faith and life” can be found in Scripture, Old and New Testament Revelation. It is the lens through which we see and understand ourselves and the world. The Westminster Confession of Faith states it this way:

• The supreme Judge, by which all controversies of religion are to be determined, and all decrees of councils, opinions of ancient writers, doctrines of men, and private spirits, are to be examined, and in whose sentence we are to rest, can be no other but the Holy Spirit speaking in the Scripture (Matt. 22:29, 31; Eph. 2:20; Acts 28:25) (WCF 1:10)

• All synods or councils, since the Apostles’ times, whether general or particular, may err; and many have erred. Therefore they are not to be made the rule of faith, or practice; but to be used as a help in both (Eph. 2:20; Acts 17:11; 1 Cor. 2:5; 2 Cor. 1:24) (WCF 31:4).

Any “tradition” that the church develops after the close of the canon, even when it is formulated in a body of doctrine like the Westminster Confession of Faith, is non-revelational. Its authority is not in any way equal to the Bible. All creeds and confessions should be subject to change based on an appeal to Scripture alone. This is especially true when it comes to eschatology where the creeds say very little and even less (nothing) in the way they came to their doctrinal conclusions.

The denial of sola scriptura is Roman Catholicism’s foundational error and convenience. The church officials can crate doctrines out of thin air and demand compliance. See Martin Luther’s “95 Theses.”

Some will argue that sola Scriptura must not become Solo Scriptura, that is, my Bible and my interpretation no matter what the creeds, confessions, and scholars might say. While these are guides, they are not Scripture. Sometimes these guides might need to be refined. This took place with the 325 Nicene Creed in 381. The Westminster Standards declared that the papacy was antichrist and man of lawlessness. Even though this belief was the prevailing position of the Reformers, the Confession was later revised.

James White makes a helpful observation in his book The Roman Catholic Controversy:

Though it may seem surprising to some, in many aspects the Christian scholar of today is closer to the original writings of the Apostles than people who lived as little as two centuries later. Why is this true? First, we have ready access to not only the entire Bible but to many of the secular writings of the day that give us important historical, cultural, or linguistic information. We have the Bible available to us in the original tongues (the vast majority of the early Church Fathers, for example, were not able to read both Hebrew and Greek, and many in the Western Church could not read either one!) as well as many excellent translations. We also have access to a vast amount of writing from earlier generations. We can read the works of men like Spurgeon or Warfield or Hodge or Machen and glean insights from these great men of God that were not available in years past. While a person living in the sixth century might have been chronologically closer to the time of Paul, he would not have had nearly as much opportunity to study the writings of Paul as we have today. We can include in our studies the historical backgrounds of the cities to which Paul was writing; we can read his letters in their original Greek. Today we can sit at a computer and with the click of the mouse have it list all the aorist passive participles in the letter to the Romans (there are 18)! These advantages allow us to be far more biblical in our teaching and doctrine.

The claim is made that cults arise out of a narrow focus of sola scriptura. Is this true? The Roman Catholic Church was able to promote their church-created doctrines because the people did not have access to the Bible in their own language. Publishing the Bible in the language of the people was a threat to the Church hierarchy and its control over the people. Bible translators were persecuted, and William Tyndale was burned at the stake for making the Bible available to the people in their own language.

King James detested the Geneva Bible, especially the notes that maintained that civil rulers were bound to follow God’s laws limiting their God-like jurisdiction in the civil sphere. For example, a marginal note for Exodus 1:19 stated that the Hebrew midwives were correct to disobey the Egyptian king’s order to kill the Hebrew babies.

King James reasoned that if it was legitimate to oppose a ruler in one area, then it was legitimate to oppose him on others. This is why King James professed, “I could never yet see a Bible well translated in English; but I think that, of all, that of Geneva is worst.”

The cult of Mormonism not only uses the Bible, but it has secondary authorities like the Book of Mormon, The Pearl of Great Price, Doctrine and Covenants, and precepts from Mormon elders. The Jehovah’s Witnesses believe the Bible as far as it is correctly translated by their unnamed translators. The Watchtower Organization tells its members what they are to believe. The Bible is interpreted for them. Their New World Translation adds words and creates a fake Greek tense like “the perfect indefinite tense” in John 8:58 to make their system work.

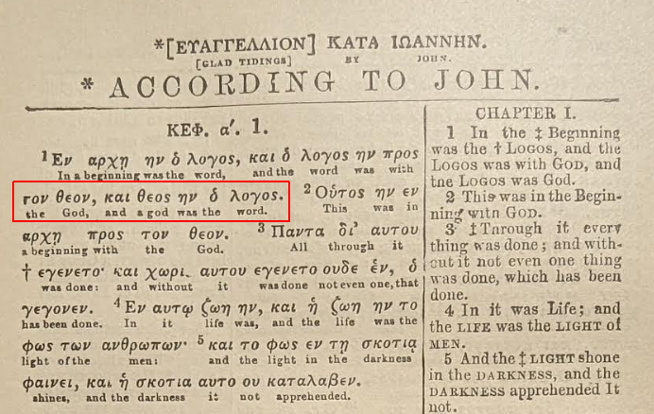

In addition, we find in their in-house translation based on James Wilson’s Emphatic Diaglott where Greek phrase “and the Word was God” in John 1:1 is translated as “the Word was a god.”

In Colossians 1:16-17 their translation adds the word “other” before “things. The text is clear that the verses read that Jesus created “all things.” But because the JW’s believe Jesus is a created being, they add the word “other” to keep their understanding of Jesus as a created being consistent.

In my opinion, solo scriptura is not a thing. All advocates of Sola Scriptura look at the long history of scholarship, study it, and appropriate what is useful comparing Scripture with Scripture. Commentaries, lexicons, scholarly journal articles, creeds, confessions, and anything else that’s available are used. This is why each year new books and articles are published going over the biblical defense of the Triune nature of God, the historicity of the resurrection of Jesus, the Bible as a “God-breathed” revelation, sola scriptura, justification, creation, and especially eschatology. Consider that the book of Revelation—an entire book of the Bible— has at least five different interpretations. While 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18 is most often interpreted as the “Second Coming” and General Resurrection, dispensationalists and others argue that what’s described is something called “the rapture of the church,” and there are five different rapture positions! It’s possible that the religious leaders who drafted the Nicene Creed did not understand that the phrase “he shall come again” most likely referred to Jesus’ coming in judgment against Jerusalem before that first century generation passed away (Matt. 24:27, 30; James 5:7-9). For a detailed study of this topic, see my books Wars and Rumors of Wars and Last Days Madness. Christians should not be consigned to hell for raising questions about what the Nicene Creed’s authors understood by “come.”

[1]Bob Moran, A Closer Look at Catholicism: A Guide for Protestants (Dallas, TX: Waco, 1986), 60.

[2]San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 1983.

[3]This line is not found in the Bible. Most of the “Hail, Mary” is a patchwork of Scripture verses that are descriptive of Mary and her special calling (Luke 1:28, 30, 48). The angel Gabriel is not uttering a prayer, nor does he encourage anyone to turn his words into a prayer.

[4]Hahn, Rome Sweet Rome, 51.

[5]Hahn, Rome Sweet Rome, 52.

[6]Greg L. Bahnsen, “The Concept and Importance of Canonicity,” Antithesis 1:5 (September/October 1990), 43.

[7]Karl Keating, Catholicism and Fundamentalism: The Attack on “Romanism” by “Bible Christians” (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 1988), 141.

[8]John A.T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press, 1976). Also see Norman L. Geisler and Frank Turek, I Don’t Have Enough Faith to be an Atheist (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2004), 237.