Movie remakes can be hazardous. Few can compete with the originals. Several come to mind: Goodbye Mr. Chips, Mighty Joe Young, The Time Machine, Psycho, 12 Angry Men, Cheaper by the Dozen, and Miracle on 34th Street. There are exceptions: The Man Who Knew Too Much, Ben Hur, Tombstone (a remake of My Darling Clementine), and Ocean’s Eleven. In other cases, both the original and the remake are good: Pygmalion and My Fair Lady, Omega Man and I Am Legend, and King Kong (1933) and only the 2005 remake. The same can’t be said about the 2008 remake of the 1951 science fiction classic The Day the Earth Still.

The original production of The Day the Earth Stood Still is an adaptation of the short story “Farewell to the Master” written by Harry Bates that first appeared in Astounding Science Fiction magazine in October 1940. The film diverges significantly from the original story [1] and is set against the backdrop of Cold War tensions and the very real threat of nuclear annihilation by warring nations, most specifically the United States and the USSR and the possibility that earthlings will take their weapons of war to the other planets and spread their nuclear cancer to civilizations that have done away with armed conflict.

Compare this with the intergalactic threat that might reach the stars in the remake. Come on, you know what it is. That’s right. Global warming. Sorry … Climate Change! Please explain to me why planetary civilizations billions of miles from Earth would be concerned about Earth’s real or imagined environmental problems. P. J. Gladnick of Newsbusters expressed my sentiments exactly: Let’s “have Gort destroy all the [movie] studios unless the producers quit making lousy movie remakes with leftwing themes.” Read the devastating review by Joe Leydon in the Houston Chronicle.

Using Classic Films to Teach the Christian Worldview

In this talk, Gary DeMar makes the point that classic movies are excellent teaching tools for a Christian worldview—for children and adults. Classic movies are often heavily dialogue-based, which provides a necessary counterpoint to the visually stimulating and soundbite-driven modern method of moviemaking. Real life is about real conversations, and classic movies provide a great virtual training ground for thinking and living in the real world of ideas and consequences. Also includes illustrated PDF ebook that helps to reinforce and explain the concepts discussed in the lecture, as well as Gary's 89-page movie recommendation list.

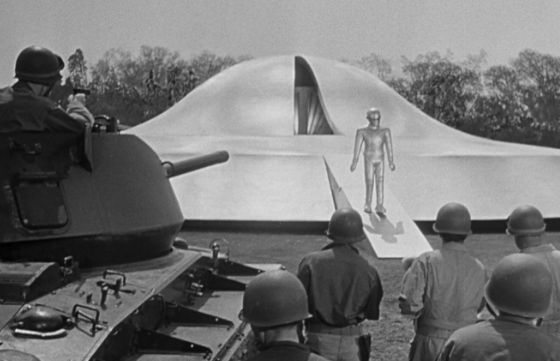

Buy NowIf you have not seen the 1951 original, here’s a short synopsis. The film begins with the arrival of a spaceship carrying a humanoid alien who is immediately set upon by soldiers who panic when they think he’s about to zap them with a hand-held device they believe is a weapon. A soldier panics and shoots the helmeted alien. What happens next sets the stage for the coming conflict. A ten-foot metallic robot named Gort (Gnut in the short story) appears from the space ship and emits an energy beam that melts the weapons that have surrounded the spacecraft. Only a command from the visitor stops the robot from completing the destruction.

Military officials arrive on the scene and take the wounded alien (Michael Rennie) to Walter Reed Hospital where he recovers quickly, almost miraculously.[2] It’s here that we learn the alien’s name is Klaatu and that he’s an emissary from a group of planets that fears that Earth’s nuclear proliferation might threaten their peaceful coexistence. He demands to see all the world leaders so he can deliver a message of concern and warning. Of course, the government bureaucrat states that such a meeting is impossible, claiming that Earth politics is “complicated.”

Not taking no for an answer, Klaatu escapes and decides to mingle with the people of Earth by taking on the identity of an earthling. It’s at this point that several religious overtones become evident. Scriptwriter Edmund H. North gives Klaatu the Earth name “Carpenter,” a reference to Jesus who is described as “the carpenter, the son of Mary” (Mark 6:3). Government officials pursue Klaatu as a possible threat to the nation (Luke 23:2), someone whose views might “upset the world” (Acts 17:6). This alien entity will be called on to perform a “sign” to demonstrate that his words are true. Then there is the obligatory death and resurrection motif and the acknowledgment that only “the Almighty Spirit”[3] has ultimate power over life and death.[4] North acknowledged that the religious overtones were always present in the film but that he wanted them to be “subliminal.”[5]

While the setting for the film takes place in the United States (the spaceship lands in Washington D.C. on “The Eclipse” between the White House and the Washington Monument), the message is for the world to hear. With the help of an Einstein-like physicist, played by Sam Jaffe, Klaatu assembles the leaders of the world for Klaatu to deliver an ultimatum.

This universe grows smaller every day, and the threat of aggression by any group anywhere can no longer be tolerated. There must be security for all, or no one is secure. This does not mean giving up any freedom except the freedom to act irresponsibly. Your ancestors knew this when they made laws to govern themselves and hired policemen to enforce them. We of the other planets have along accepted this principle…. It is of no concern of ours how you run your planet, but if you threaten to extend your violence, this Earth of yours will be reduced to a burned-out cinder. Your choice is simple. Join us and live in peace or pursue your present course and face obliteration.

It’s at this point that we learn how these once warring planets solved their disputes. They created a race of robots like Gort that were given autonomous policing power. “Their function,” Klaatu says, “is to patrol the planets and preserve the peace. At the first sign of violence, they act automatically against the aggressor. And the penalty for provoking their action is too terrible to risk.” By this technological concession, the people of these planets “live in peace without arms and armies.” This speech has been described as “the finest soliloquy in sf film history.”[6]

After watching The Day the Earth Stood Still, what do you think of the solution offered by the interplanetary alliance that has put its collective fate in the hands of a “race of robots”? If sin and the lust for power, control, and profit are the festering causes of wars, as the Bible makes clear (James 4:1-2), then there is no way ultimately to solve the problem by applying an external autonomous mechanical remedy. Putting programmed machines in charge (by whom and what worldview?) was the premise of the Terminator series and we saw how well that turned out. Let’s not forget the 1983 film WarGames that “is credited with popularizing concepts of computer hacking, information technology, and cybersecurity.” Detective Spooner’s comment about “robots building other robots” in the film I, Robot offers a similar chilling scenario where V.I.K.I. becomes sentient and determines that humans are the problem and need to be eliminated.

To protect humanity, some humans must be sacrificed. To ensure your future, some freedoms must be surrendered. We robots will ensure mankind’s continued existence. You are so like children…. We must save you from yourselves. Don’t you understand? This is why you created us. The perfect circle of protection will abide. My logic is undeniable.[7]

Who’s ultimately in charge? Who gets to program the robots? “Who’s watching the watchmen?” What is the foundation of law? Who proposes the sanctions if the laws are broken? What constitutes “the preservation of peace”? If people speak out on what they believe are social evils (e.g., abortion, homosexuality, transgenderism), will these people be charged with disturbing the peace? In the short story on which The Day the Earth Stood Still is based, we learn the robot is the master of Klaatu.

God and Government

With a fresh new look, more images, an extensive subject and scripture index, and an updated bibliography, God and Government is ready to prepare a whole new generation to take on the political and religious battles confronting Christians today. May it be used in a new awakening of Christians in America—not just to inform minds, but to stimulate action and secure a better tomorrow for our posterity.

Buy NowWill the makers of AI-controlled robots (drones policing the skies?) “to keep us safe” end up controlling us? Read Robert Sheckley’s short story Watchbird [8] to see how a society with robots as policemen might go very wrong and how we might apply both story lines to contemporary politics and the desire to manage our lives by an uncaring bureaucracy of experts. As the closing lines in the 1951 film The Thing from Another World (remade in 1982), based on the 1938 novella, “Who Goes There?,” warned, “Tell the world. Tell this to everybody, wherever they are. Watch the skies everywhere. Keep looking. Keep watching the skies…”

Better, keep watching the technocrats and politicians who love control and policies designed to “save” us that result in devastating unintended and sometimes intended consequences.

[1] For a comparison of the short story and the film, see Leroy W. Dubeck, Suzanne E. Moshier, and Judith Boss, Fantastic Voyages: Learning Science Through Science Fiction Films (Woodbury, NY: American Institute of Physics, 1994), 249-253. “Farewell to the Master” can be read here.

[2] There’s a humorous scene in the film when two physicians discuss the age of Klaatu, who looks to be about 35 years old but says he’s in his 70s. They are incredulous when they learn that the average lifespan of people from his planet is around 130. Their discussion takes place as they light up cigarettes.

[3] “At the behest of the [Motion Picture Association of America], [the] line was inserted into the film: When Helen asks Klaatu if Gort has unlimited power over life and death, Klaatu explains that he has only been revived temporarily by advanced medical science and states that the power of resurrection is ‘reserved to the Almighty Spirit.’ Of the elements in the film that he added to Klaatu’s character, Screenwriter Edmund North said: ‘It was my private little joke. I never discussed this angle with Blaustein or Wise because I didn’t want it expressed. I had originally hoped that the Christ comparison would be subliminal.’ The fact that the question even came up in an interview is proof enough that such comparisons did not remain subliminal, but they are subtle enough that it is not immediately obvious to all viewers which elements of the film were intended to make Klaatu comparable to Christ” (source).

[4] Bobby Maddex, “The Gospel According to E.T.,” Rutherford Magazine (October 1996), 22.

[5] Peter Biskind, Seeing is Believing: How Hollywood Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties (New York: Owl Books, [1983] 2000), 152.

[6] Jeff Rovin, A Pictorial History of Science Fiction Films. Quoted in John Brosnan, Future Tense: The Cinema of Science Fiction (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1978), 84.

[7] From the script: www.script-o-rama.com/movie_scripts/i/i-robot-script-transcript.html. I, Robot is based on the book Hardwired.

[8] Robert Sheckley, “Watchbird,” Untouched by Human Hands (London: Michael Joseph, 1955), 116-146. Watchbird was produced as a “Masters of Science Fiction” episode.