Please help us reach $10K in donations for a matching grant

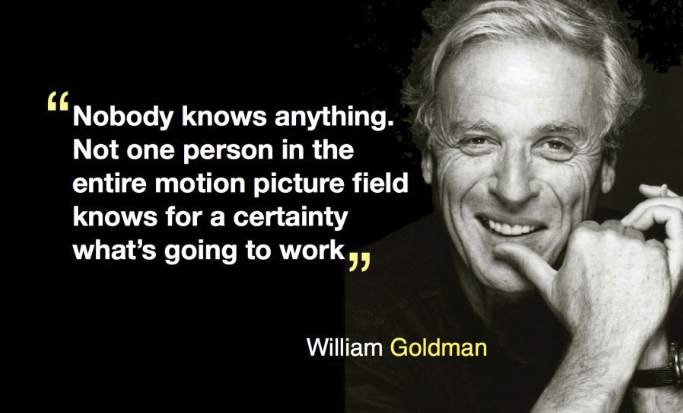

William Goldman, not to be confused with William Golding, author of Lord of the Flies, sums up the problem of attempting to be certain about the success of a film this way: “Nobody knows anything.” Goldman should know. He was a successful novelist and screenwriter with several Academy Awards and big screen blockbusters to his credit. Goldman was not saying that Hollywood types are generally ignorant or stupid. He was pointing out that they are not omniscient. They don’t have enough knowledge about people and their tastes to know whether a film will be a success. It’s always been that way, and it will always be that way.

“Testing theories against evidence never ends. The National Academy [of Sciences] booklet [on science] correctly states that ‘all scientific knowledge is, in principle, subject to change as new evidence becomes available.’ It doesn’t matter how long, or how many scientists currently believe it. If contradictory evidence turns up, the theory must be reevaluated or even abandoned.”[1]

Man in the Dock

In a biblical defense of the Christian faith, God is not the one on trial. Modern man, however, does not see it this way. C. S. Lewis points out:

The ancient man approached God (or even the gods) as the accused person approaches his judge. For the modern man the roles are reversed. He is the judge: God is in the dock [the enclosure where a prisoner is placed in an English criminal trial]. He is quite a kindly judge: if God should have a reasonable defence for being the god who permits war, poverty and disease, he is ready to listen to it. The trial may even end in God’s acquittal. But the important thing is that Man is on the Bench and God in the Dock.[2]

How can a finite, fallible, and fallen person ever be a qualified judge of eternal things? How is it possible that the creature can legitimately question the Creator? God asks Job: “Will the faultfinder contend with the Almighty? Let him who reproves God answer it” (Job 40:1). Job responded, knowing the limitations of his own nature, the only way he could: “Behold, I am insignificant; what can I reply to Thee? I lay my hand on my mouth” (40:4). God asks Job a series of questions that demonstrate how limited he is in knowledge and experience. God inquires of Job: “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth! Tell Me, if you have understanding. Who set its measurements, since you know?” (38:4). Job was trying to figure out the world and the way it works based on his own limited frame of reference. This is an impossible and immoral task.

The Fool and His Folly

Given that neutrality is impossible, how is the Christian apologist to argue with someone who holds a contradictory set of assumptions? Christians are commanded not to “answer a fool according to his folly.” Why? He’ll be “like him” in his misguided assumptions and will also be classified as a “fool” (Prov. 26:4). The Bible assumes that worldviews based on presuppositions that are contrary to the Bible are foolishness. This is why Scripture states emphatically and without apology that the professed atheist is a “fool” (Psalm 14:1; 53:1). How can an insignificant creature who is smaller than an atom when compared to the vastness of the universe be so dogmatic?

An apologetic methodology that claims a Christian should be “open,” “objective,” and “tolerant” of all opinions when the faith is attacked is like a person who hopes to stop a man from committing suicide by taking the hundred-story plunge with him, hoping to convince the lost soul on the way down. No one in his right mind would make such a concession to foolishness. But Christians do it all the time when they adopt the operating presuppositions of unbelieving thought as if they were neutral assumptions about reality.

Against All Opposition

There are no "neutral" assumptions about reality. The starting point is the God of the Bible. The Bible begins with this foundational presupposition: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen. 1:1). Against All Opposition lays out the definitive apologetic model to help believers understand the biblical method of defending the Christian faith.

Buy NowWhile the Bible maintains that the Christian apologist is prohibited from adopting the starting point of unbelieving thought, he is encouraged to show the unbeliever the end result of his foolish philosophical principles if they are consistently followed. As defenders of the only true faith, we are to “answer a fool as his folly deserves, lest he be wise in his own eyes” (Prov. 26:5). That is, we are to put the unbeliever’s worldview to the test, showing how absurd it is when followed consistently. A world without God and moral absolutes leads to despair and moral anarchy.

We All Believe in Something

All worldviews are belief systems, even all the anti-worldviews. A person does not have to believe in God to be considered religious. “Richard Dawkins has publicly admitted: ‘I believe, but I cannot prove, that all life, all intelligence, all creativity and all “design” anywhere in the universe, is the direct or indirect product of Darwinian natural selection.’”[3] Dawkins was not a consistent atheist. He borrowed Christian moral capital to keep himself alive. Watch him squirm when asked about Islam.

John H. Dietrich (1878-1957), a Unitarian minister who “accepted the theory of evolution and revised the worship service so that the Apostles Creed was delineated and secular readings were incorporated,” admitted that he was a religious humanist.

For centuries the idea of God has been the very heart of religion; it has been said, “No God, no religion.” But humanism thinks of religion as something very different and far deeper than any belief in God. To it, religion is not the attempt to establish right relations with a supernatural being, but rather the unpreaching and aspiring impulse in a human life. It is the striving for its completest fulfillment, and anything which contributes to this fulfillment is religious, whether it be associated with the idea of God or not.[4]

Since we are all limited in knowledge and restrained by our inability to be everywhere (omnipresence) and know everything (omniscience), an atheist puts forth his claim that God does not exist in terms of a faith commitment. When the late Carl Sagan wrote, “The cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be,”[5] he was making a declaration of faith, a statement of his ultimate presupposition. There is no way he could be assured that God does not exist based on his limited knowledge and experience and the limited knowledge and experience of others. Sagan admitted that “the size and age of the Cosmos are beyond ordinary human understanding.”[6] Even so, he was convinced that the material world is all that exists. He believed one thing to be true and dismissed any worldview that did not conform to it without having all the facts or the ability to understand fully what he did know. Sagan’s assertions do not conform to reality. Greg Koukl describes the inevitability of belief:

Everybody believes something, and even what appears to be a rejection of all beliefs is a kind of belief. We all hold something to be true. Maybe what you hold true is that nothing else is true, but that is nonetheless something you believe.

Even if you are agnostic, you believe that it is not possible to know things about ultimate issues like the existence of God. You believe in the justifiability of your agnosticism—your uncertainty—and you have a burden of proof to justify your unwillingness to decide. There is nowhere someone can stand where he or she has no beliefs. If you reject Christianity, there is something else that you end up asserting by default.[7]

Once a person rejects Christianity, he has not set himself free from the concept of faith. He has only transferred his faith to something or someone else.

Why It Might Be OK to Eat Your Neighbor

The most damning assessment of a matter-only cosmos devoid of a Creator is that we got to this place in our evolutionary history by acts of violence whereby the strong conquered the weak with no one to support or condemn them. Why It Might Be OK to Eat Your Neighbor repeatedly raises the issue of accounting for the conscience, good and evil, and loving our neighbor. It’s shocking to read what atheists say about a cosmos devoid of meaning and morality.

Buy NowFor Sagan, the cosmos is god-like, a glorious accidental substitute for what he assured himself were ancient, pre‑scientific mythical beliefs about the deity and the origin and nature of the universe. The very idea of a personal God, in Sagan’s worldview, is simply “the dreams of men.”[8] Even so, Sagan’s worldview was fundamentally just as religious as that of a theist. He did not entertain the possibility that his own worldview was simply the dreams of an atheist. Sagan’s starting point—his ultimate presupposition—evaluates all that he sees or doesn’t see in the cosmos. There is no more fundamental belief. All that follows in the Cosmos worldview is measured by his one‑sentence, presuppositional yardstick: “The cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be.” William Fix doesn’t allow Sagan to get away with his supposed claim of “objectivity”:

When Sagan excludes even the possibility that a spiritual dimension has any place in his cosmos—not even at the unknown, mysterious moment when life began—he makes accidental evolution the explanation for everything. Presented in this way, evolution does indeed look like an inverted religion, a conceptual golden calf, which manages to reek of sterile atheism. It is little wonder that many parents find their deeper emotions stirred if they discover this to be the import of Johnny’s education.[9]

Sagan worshiped an eternal cosmos that he presupposed is an evolutionary substitute for the eternal God of the Bible who gives life and meaning to the cosmos. Sagan said it like this: “It is the universe that made us…. We are creatures of the cosmos…. Our obligation to survive and flourish is owed, not just to ourselves, but also to that cosmos, ancient and vast, from which we spring.”[10] The primordial biotic soup nourished our ancient ancestors as they emerged from that first ocean of life. These memories, according to Sagan, are eternally etched on our evolved psyche.

The ocean calls. Some part of our being knows this is from where we came. We long to return. These aspirations are not, I think, irreverent, although they may trouble whatever gods may be.[11]

How can anyone know this? Such a belief is nothing more than a hypothesis, and not a very good. This isn’t science. It’s stream of consciousness mysticism. Sagan believed that there are no transcendent personal “gods” in his universe, only “accidents”[12] that somehow developed into design and meaning.

At times, however, Sagan muses rhapsodic over a seemingly benign reverence for the cosmos that hints at a deep religious commitment to atheism and elements of paganism. “Our ancestors worshipped the sun,” he reflects, “and they were far from foolish. It makes good sense to revere the sun and the stars, because we are their children.” But who made the cosmos? How did the cosmos get here? No design, no order, no organized information, and a lack of complexity can’t “create” anything.

[1] Jonathan Wells, Icons of Evolution: Science or Myth? Why So Much of What We Teach About Evolution is Wrong (Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, 2000), 2-3.

[2] C.S. Lewis, “God in the Dock,” in God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1970), 244.

[3] “Dawkins made this remark in response to a question posed by the New York Times to a number of prominent scientists: ‘What do you believe what you cannot prove?’ The Times published the responses on January 4, 2005.” Quoted in Robert Royal, The God that Did Not Fail: How Religion Built and Sustains the West (New York: Encounter Books, 2006), xii, 277.

[4] Quoted in Cornelius Loew, Modern Rivals to Christian Faith (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press, 1956), 11.

[5] Carl Sagan, Cosmos (New York: Random House, 1980), 4.

[6] Sagan, Cosmos, 4.

[7] Greg Koukl, “You’ve Got to Believe Something,” The Plain Truth (January/February 1999), 39.

[8] Sagan, Cosmos, 257.

[9] William R. Fix, The Bone Peddlers: Selling Evolution (New York: Macmillan, 1984), xxiv.

[10] From the 13-hour long television presentation of Cosmos aired in the fall of 1980. Quoted in Richard A. Baer, Jr., “They Are Teaching Religion in the Public Schools,” Christianity Today (February 17, 1984), 12.

[11] Sagan, Cosmos, 5.

[12] Sagan, Cosmos, 30.