When a person loses hope and does not see meaning in this life, inevitable consequences follow. Giving up on life is the result of life having no meaning. Why bother if we are nothing but a conglomeration of atoms and molecules animated by an electrical charge? There’s no meaning in that. How does a civilization survive and grow when previous generations strip life of meaning. A life without meaning leaves nothing behind for the next generation that is equally meaningless. Legacies don’t matter. The great cathedrals in Europe are a testimony to the legacy of meaning. The story of Elzeard Bouffier, an allegorical tale by French author Jean Giono, published in 1953, is an illustration of the meaning of life that carries on the efforts of the past and moves life forward.

The story itself is said to have had such an inspiring effect on readers because of its symbolic value rather than its literal meaning. For the story shows how a small, sustained, selfless and consistent action of just one man can commit to restoration, growing, new development. Over decades (between 1913 and 1947), the man plants hundreds of thousands of seeds from a variety of native trees in a vast area around his cottage. As a result, the barren, arid region is revived and eventually his work is noticed and protected by the government.

Why bother if life has no meaning, if we are only impersonal cogs in a perpetual motion machine going who knows where to no meaningful end?

Why It Might Be OK to Eat Your Neighbor

The most damning assessment of a matter-only cosmos devoid of a Creator is that we got to this place in our evolutionary history by acts of violence whereby the strong conquered the weak with no one to support or condemn them. Why It Might Be OK to Eat Your Neighbor repeatedly raises the issue of accounting for the conscience, good and evil, and loving our neighbor. It’s shocking to read what atheists say about a cosmos devoid of meaning and morality.

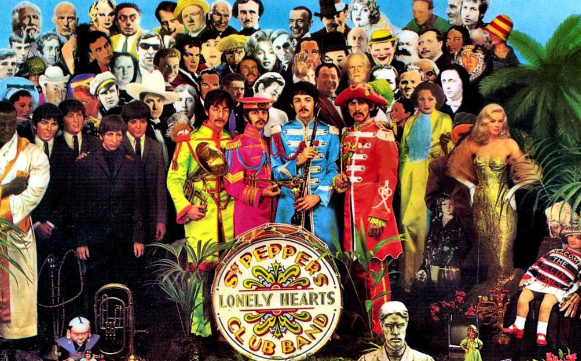

Buy NowAldous Huxley (1894-1963) was the grandson of Thomas Huxley, “Darwin’s Bulldog,” and the author of Brave New World (1932). His book The Doors of Perception (1954) was the inspiration for Jim Morrison and the rock band “The Doors.” Huxley appears on the album cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. He was an influential figure in the heyday of eternal optimism built on the shifting sands of relativism.

Huxley had the fateful distinction of dying the same day as John F. Kennedy and C.S. Lewis on November 23, 1963. The announcements of their deaths were lost in the rush of news surrounding the assassination of the president.

Huxley went through several worldview changes in his productive literary life. In the 1940s, he began to question the absoluteness of the sciences. He wrote the following in his earliest work of philosophy Ends and Means published in 1937:

[I]n recent years, many men of science have come to realize that the scientific picture of the world is a partial one—the product of their special competence in mathematics and their special incompetence to deal systematically with aesthetic and moral values, religious experiences and intuitions of significance.[1]

This is remarkable foresight given the rise of the absoluteness of the field of science as it is presented today. We’re being told that there is nothing beyond the scientific enterprise. Huxley knew better. Keep in mind that he was not speaking as a Christian fundamentalist. His grandfather was Charles Darwin’s staunchest defender described as “Darwin’s Bulldog.” His brother Julian (1887-1975) was an eminent evolutionary biologist.

Huxley never abandoned his humanist worldview, but he did question some of its implications. He has a well thought out critique of what he calls the “philosophy of meaninglessness.” There were those who carried their materialism into dark corners. He admits that he was one of them. What was at first considered to be liberation became a license for moral degradation:

For myself, as, no doubt, for most of my contemporaries, the philosophy of meaninglessness was essentially an instrument of liberation. The liberation we desired was simultaneously liberation from a certain political and economic system and liberation from a certain system of morality. We objected to the morality because it interfered with our secular freedom; we objected to the political and economic system because it was unjust. The supporters of these systems claimed that in some way they embodied the meaning (a Christian meaning, they insisted) of the world. There was one admirably simple method of confuting these people and at the same time justifying ourselves in our political and erotic revolt: we could deny that the world had any meaning whatsoever.[2]

A similar thing is happening today. Christianity is denounced so all moral restrictions can be removed. Of course, few are consistent with their modernized worldview of meaninglessness. If they were, the implications for them and society would be even more troubling than it is today. Think of the 2013 film World Z, but no with virus-infected zombies ravaging everything in sight. The ravaging is taking place from the sewage of putrefied worldviews in the name of moral autonomy.

At the same time, these moral anarchists want the luxury of moral freedom so they can engage fully in their “erotic revolt” and deny it for others. In a November 27, 1802, letter to the editor of The Temple of Reason, a “Rich Deist” wrote, “Very few rich men; or, at least men in the higher grades of society, and who receive a liberal education, care anything about the Christian religion. They cast off the yoke of superstition themselves; yet, for the sake of finding obedient servants, they would continue to impose it on the poor.”[3]

But these moral anarchists cannot control their “erotic revolt.” In time, others will imbibe the full measure of their philosophy. It’s the vampire theme compounded. Once an “erotic revolt” starts, there’s no way to stop it. Once the leavening of the gospel is denied, society takes on the image of the new revolution and carries it forward with startling consistency. The Marquis De Sade’s “philosophy was the philosophy of meaninglessness carried to its logical conclusion,” Huxley wrote. “Life was without significance. Values were illusionary and ideals merely the inventions of cunning priests and kings. Sensations and animal pleasures alone possessed reality and were alone worth living for. There was no reason why anyone should have the slightest consideration for anyone else. For those who found rape and murder, rape and murder were fully legitimate activities. And so on. . . . De Sade is the one completely consistent and thoroughgoing revolutionary in history.”[4]

Reestablishing meaning requires a worldview overall. The new birth is the first step because without life there is no new life. But this world is meaningful. Many Christians have been told the opposite. To disdain this world is the true meaning of life. Too often we forget that this is God’s good creation (1 Tim. 4:1-4). It has meaning because it is God’s creation. We should never disdain what God says is holy and good.

Thinking Straight in a Crooked World

The nursery rhyme "There Was a Crooked Man" is an appropriate description of how sin affects us and our world. We live in a crooked world of ideas evaluated by crooked people. Left to our crooked nature, we can never fully understand what God has planned for us and His world. God has not left us without a corrective solution. He has given us a reliable reference point in the Bible so we can identify the crookedness and straighten it.

Buy Now[1] Aldous Huxley, Ends and Means: An Enquiry into the Nature of Ideals and into the Methods Employed for their Realization (London: Chatto & Windus, [1937] 1951), 268-269.

[2] Huxley, Ends and Means, 273.

[3] Quoted in Henry M. Morais, Deism in Eighteenth-Century America (New York: Russell & Russell, 1960), 14-15.

[4] Huxley, Ends and Means, 270.