We’re entering a time when operating assumptions about the real and unreal are being put to the test. All ideas have consequences, good or bad. There is no third way. Those who deny the existence of God must experiment with operating assumptions. They can never know what will work because their worldview does not operate in terms of fundamental truths. Their “truths” are manufactured as we seen with the LGBT+ crowd and climate alarmists. Science was often said to be the ultimate presupposition, but that is no longer true even among some scientists.

Physicalism still reigns supreme, but it can’t account for anything that is not physical. Consider the following:

I can add intelligibility, purpose, truth, knowledge, coherence, the uniformity of nature, and objective value and worth.

Anyone who claims that human beings are only meat machines is delusional. Their delusion is contained because most physicalists are not consistent. We are thankful for that. There is more to us than the physical properties of DNA.

If you’ve ever seen the 1957 film “The Incredible Shrinking Man,” based on Richard Matheson’s 1956 novel The Shrinking Man, the film ends with the central character, Scott (played by Grant Williams), accepting his fate as he shrinks to subatomic size but does not deny his humanity.

Would he find ethical norms listed as he shrinks? Justice, good and evil, and the other forementioned non-physical realities? As he becomes even smaller, we hear his thoughts as the film ends: “All this vast majesty of creation, it had to mean something. And then I meant something too. Yes, smaller than the smallest, I meant something too. To God, there is no zero. I still exist.” Why? Because we are more than matter.

Using Classic Films to Teach the Christian Worldview

Classic movies are often heavily dialogue-based, which provides a necessary counterpoint to the visually stimulating and soundbite-driven modern method of moviemaking. Real life is about real conversations, and classic movies provide a great virtual training ground for thinking and living in the real world of ideas and consequences.

Buy NowThis brings me to a film adaptation to Agatha Christie’s Hallow’en Party titled A Haunting in Venice (2023) The following is from Collin Garbarino’s review in World magazine:

In Christie’s novels, Poirot is partly motivated by a sense of divine justice, but [Kenneth] Branagh’s Poirot has confronted the problem of evil and lost his faith.

The previous movies [Murder on the Orient Express deals with revenge and Death on the Nile greed while A Haunting in Venice is about whether there’s something beyond us] set up this world-weary version of Poirot. He has a brilliant mind, but he’s tortured by loss. He says he doesn’t believe in God, but he wishes he could because without God life has no meaning. It’s his disbelief that’s driven him into his reclusive retirement. If in the end life has no purpose, what’s the point of searching for truth and justice?[1]

Again, presuppositions matter. Why bother with a world that can’t account for truth or justice? You can only go so far with wishful thinking.

Why It Might be OK to Eat Your Neighbor

Love your neighbor or eat him? Why It Might Be OK to Eat Your Neighbor repeatedly raises the issue of accounting for the conscience, good and evil, and loving our neighbor. It’s shocking to read what atheists say about a cosmos devoid of meaning and morality.

Buy NowThe following is from William Jennings Bryan’s Summation at the 1925 Scopes Trial that’s included in my recently published book Why It Might be OK to Eat Your Neighbor. For Bryan, the Scope’s Trial was more about the ethical implications of Darwinism than how old the earth is.

Science is a magnificent force, but it is not a teacher of morals. It can perfect machinery, but it adds no moral restraints to protect society from the misuse of the machine. It can perfect machinery, but it adds no moral restraints to protect society from the misuse of the machine. It can also build gigantic intellectual ships, but it constructs no moral rudders for the control of storm-tossed human vessel. It not only fails to supply the spiritual element needed but some of its unproven hypotheses rob the ship of its compass and thus endanger its cargo. In war, science has proven itself an evil genius; it has made war more terrible than it ever was before. Man used to be content to slaughter his fellowmen on a single plane, the earth’s surface. Science has taught him to go down into the water and shoot up from below and to go up into the clouds and shoot down from above, thus making the battlefield three times as bloody as it was before; but science does not teach brotherly love. Science has made war so hellish that civilization was about to commit suicide; and now we are told that newly discovered instruments of destruction will make the cruelties of the late war seem trivial in comparison with the cruelties of wars that may come in the future. If civilization is to be saved from the wreckage threatened by intelligence not consecrated by love, it must be saved by the moral code of the meek and lowly Nazarene. His teachings, and His teachings alone, can solve the problems that vex the heart and perplex the world.

Christian philosopher Greg Koukl points out the problem of how to account for and promote “good” and rejecting “evil” in a world without God:

In rejecting God, the atheist still has to face evil in the world and explain where it came from. Can he? I doubt it. But the atheist also has to explain where good comes from. If there is no God, it’s hard to make any sense out of either of those concepts. If there is no God, then there is nothing that is evil or good. You have to have a standard of good and evil that stands outside of us to define what evil and good actually are.[2]

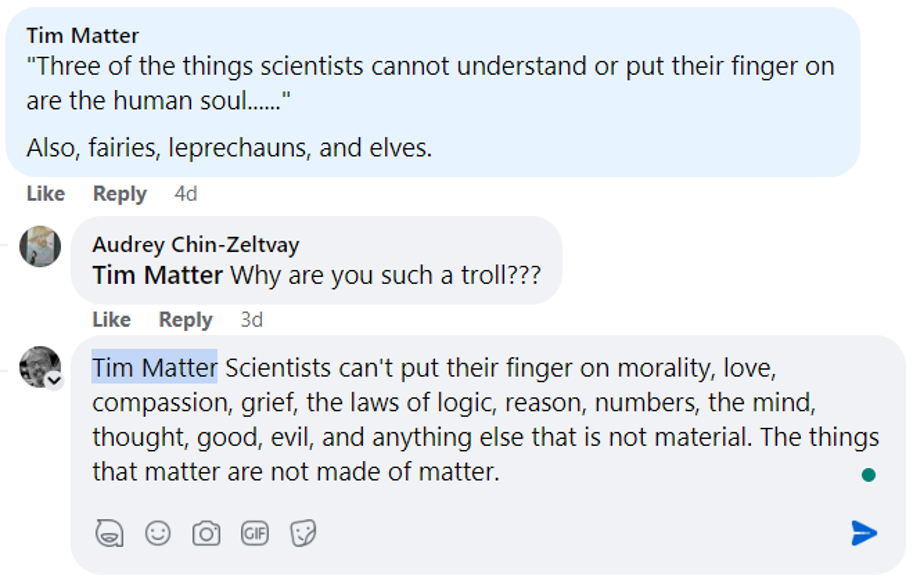

The issue is not whether non-believers can do good but how does the physicalist account for good and so much more. Claiming that God exists is akin to believing in Leprechauns, fairies, and elves is a huge category mistake. As far as I know, no one is ascribing the origin of moral absolutes, love, compassion, justice, reason logic, and the mind to Leprechauns, fairies, and elves.

[1]Collin Garbarino, “A Haunting in Venice,” World (October 7, 2023), 34. The online version of the article can be found here: https://wng.org/articles/a-haunting-in-venice-1694796969

[2]Greg Koukl, “You’ve Got to Believe Something,” The Plain Truth (January/February 1999), 39.