Gary concludes his conversation with Jeremy Stalnecker about biblical worldview.

All of us think in terms of worldviews. A worldview is the way each of us looks at and evaluates everything that is seen, experienced, or thought about. Worldviews have been described as a web of beliefs that we carry around in our heads that becomes an “interconnected system of all that we believe. Tied together more or less coherently in this web are all of the beliefs we hold as true. These include the basic beliefs (such as ‘I exist’ and ‘life is worthwhile’) and the more trivial ones (such as ‘I hope we won’t have liver again’). No belief exists in isolation; each belief is connected with all others in one big network.”[1]

Every person has a worldview that daily systematizes and organizes tens of thousands of bits of seemingly unrelated pieces of information and varied experiences. In fact, without a coherent worldview, these informational fragments would remain unrelated, disjointed, and ultimately meaningless.

A person’s worldview is the collection of his presuppositions or convictions about reality, which represent his total outlook of life. Nobody is without such fundamental beliefs, and yet many people go through life unaware of their presuppositions. Operating at the unconscious level, their presuppositions remain unidentified and unexamined. The result is that people generally fail to recognize how their worldviews govern every dimension of their lives: the intellectual life (what they believe is true about themselves and their place in history); the physical (how they treat or mistreat their bodies by eating, sleeping, and exercising); the social (how they interact with friends and enemies, the rich and the poor, the strong and the weak); the economic (why they work and how they spend their wages); and the moral (what ethical guidelines and obligations direct their thinking about justice and issues such as abortion and euthanasia).[2]

As worldviews develop and mature over time, they sort and interpret familiar information instantaneously. New information is evaluated in terms of what is already known and thought to be true. If some new facts or experiences do not fit within the boundaries of our already established worldview, they are either rejected, ignored,[3] or reinterpreted to make them conform. Someone who understands the finite nature of all creatures, might put aside any unfamiliar findings until additional information can be gathered and evaluated to make sense of the new data in light of what is already known. After some time of thoughtful consideration, adjustments might have to be made to our worldview web to accommodate the new information.

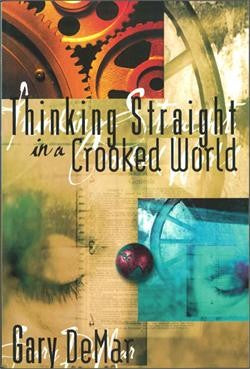

Thinking Straight in a Crooked World

The nursery rhyme ‘There Was a Crooked Man’ is an appropriate description of how sin affects us and our world. We live in a crooked world of ideas evaluated by crooked people. Left to our crooked nature, we can never fully understand what God has planned for us and His world. God has not left us without a corrective solution. He has given us a reliable reference point in the Bible so we can identify the crookedness and straighten it.

Buy NowGary concludes his conversation with Jeremy Stalnecker about biblical worldview. How do we train our minds to “think biblically”? How do we answer cultural and ethical problems with biblical truth? It’s not easy, but Christians should want to put in the work to understand and teach others how to apply biblical truth to every area of life.

Click here for today’s episode

Click here to browse all episodes of The Gary DeMar Podcast

[1] Winfried Corduan, No Doubt About It: The Case for Christianity (Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1997), 66.

[2] W. Andrew Hoffecker, “Preface: Perspective and Method in Building a World View,” Building a Christian World View: God, Man, and Knowledge (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1986), ix–x.

[3] For example, Planned Parenthood’s purposeful non-response to George Grant’s Grand Illusions: The Legacy of Planned Parenthood, 4th ed. (Nashville, TN: Cumberland House, 2000), xxvi–xxx.