Most Christians cannot read and translate Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, the languages of the Bible. As a result, for most of us, we are dependent on translations. Vernacular translations began early. The Latin Vulgate was mostly the work of Jerome (345-420). The Vulgate was adopted as the Bible translation of the Western Church. It was the first book printed using JohannesGutenberg’s printing press in the 14th century. Martin Luther translated the Bible into German in 1522 with the result that it unified the German language. There was ecclesiastical resistance to English translations beginning with John Wycliffe’s complete translation in 1382. William Tyndale’s translation was the first English version to use the Hebrew and Greek texts rather than the Vulgate. For his work, Tyndale was strangled and burned at the stake. In 1611, 47 scholars had produced the King James Version of the Bible, often referred to as the Authorized Version. It, too, drew extensively from Tyndale’s work.

The King James translation surpassed the 1560 and later editions of the Geneva Bible in popularity. A standardized and adopted English translation had the effect of unifying English-speaking Christians when it came to Bible reading, memorization, and worship.

In some cases, the translations, even the KJV, are not as literal as they could be. The goal of the translator should be to stay as close to the original text as is linguistically possible by making judicious translation decisions that maintain the integrity of the words used by the biblical authors. When a literal translation is not made, the reader should be notified and told why. This is done in some translations like the KJV and the NASB that italicize words that are not in the Hebrew or Greek texts.

A Beginner's Guide to Interpreting Bible Prophecy

With so much prophetic material in the Bible — somewhere around 25% of the total makeup of Scripture — it seems difficult to argue that an expert is needed to understand such a large portion of God’s Word and so many “experts” could be wrong generation after generation. If God’s Word is a lamp to our feet and a light to our path” (Psalm 119:105), how do we explain that not a lot of light has been shed on God’s prophetic Word and with so little accuracy? A Beginner’s Guide to Interpreting Bible Prophecy has been designed to help Christians of all ages and levels of experience to study Bible prophecy with confidence.

Buy NowThis is different from not translating a word that’s in the text. For example, John 3:3 reads “born from above” rather than “again.” Logically this is still a “second birth,” but “from above” conveys the origin and nature of the new birth in a way that is not conveyed by “again.” This more literal translation might help to answer someone who claims the Bible teaches reincarnation.[1]

In addition, knowing that the Greek literally reads “from above” might lead us to pull the entire chapter together by way of John the Baptist’s testimony in John 3:31 that Jesus is the one “who comes from above” and “became flesh and tabernacled among us” (1:14).

Second Timothy 3:16 is most often translated as “All Scripture is inspired by God.” The literal translation of the Greek theopneustos is “God-breathed.” “Inspired” gives the impression that something is done to the writings (graphē). Unfortunately, the word “inspired” is also often used to describe the effect an action, work, or encounter has on a person for motivation or an uplifting feeling. “God-breathed” stresses the origin of the revelation as God’s own words. The New International Version, usually a less than a literal translation, renders theopneustos as “God-breathed.”

It might be helpful to know that John 1:14 reads as the “Word became flesh” and “tabernacled among us” (cf. Ex. 25:8), considering what we read in John 2:19-22 that Jesus identifies Himself as the new and permanent temple. “Dwelled among us” does not have the same link to language found in the Hebrew Scriptures. This might not make sense to a new reader, but it is important for someone wanting to study the Bible for its theological meaning.

Having a basic knowledge of Greek is helpful and can go a long way to help with interpretation in terms of what the Bible literally says. The Greek alphabet can be learned in a few hours. You can be reading the NT in Greek within a week, although you might not know what you are reading since learning vocabulary and grammar take more time. But with a Greek-English interlinear cross-referenced to Strong’s numbering system and a basic dictionary, you will be able to determine the meaning of each Greek word.

A concordance lists every word in the Bible and gives its English translation. A concordance like Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance also serves as a basic Bible dictionary. Strong’s comes in printed and electronic forms. It is keyed to the KJV. Different Greek words are often translated by a single English word. Consider the word “world” (2889: kosmos: John 3:16), (3625: oikoumenē: Luke 2:1), (165: aion: 2 Cor. 4:4). The KJV has “the end of the world” in Matthew 24:3 where the Greek word aiōn is used and not kosmos. It can be confusing when reading an eschatological chapter like Matthew 24. “World” and “age” have very different meanings in terms of eschatology.

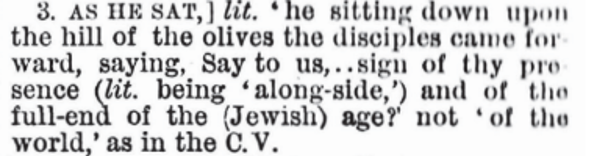

This is why a literal translation of the Bible is helpful. Robert Young, in addition to the publication of his Analytical Concordance to the Bible, he also published several editions of his Literal Translation of the Bible. He also published the Concise Critical Bible Commentary that was Specially Designed for Those Teaching the Word of God. It’s his NT version of his Concise Critical Bible Commentary that American Vision is republishing. It’s a real eye-opener when it comes to words often mistranslated and sometimes not translated in popular Bible translations. The following is Young’s comment on Matthew 24:3:

He also translates the Greek word parousia as “presence,” as do the lexicons, rather than “coming.” This is important since there is a different Greek word (ἐρχόμενον/erchomenon) that is more accurately translated as “coming.”

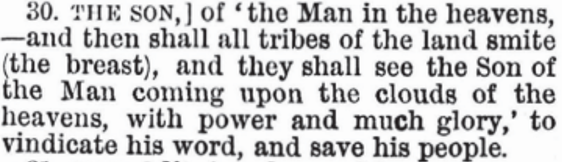

The careful reader will note that Young has “tribes of the land” rather than “tribes of the earth.” This translation fits will with the local geography described, the audience (the use of the second person plural), cultural conditions (flat roofs and Sabbath regulations), and the prophecy concerning the destruction of the temple.

Matthew 24:14 is most often translated, “And this gospel of the kingdom shall be preached in all the world….” The casual Bible reader might conclude that the fulfillment of this verse is in our future since the Gospel was not preached throughout the whole world in Jesus’ day. But kosmos is not used in Matthew 24:14. Matthew uses oikoumenē which means “inhabited earth,” “Roman empire,” “Roman world” or “limited political boundary.” Here’s Young’s comment (the verse number should be 14).

As you can imagine, a literal translation of Matthew 24:14 puts an entirely new perspective on Jesus’ prophecy.

Oikoumenē is used in Luke 2:1, Acts 11:28, and other places in the NT. The NASB translates oikoumenē in Luke 2:1 as “inhabited earth” with a marginal note that reads “I.e., the Roman empire.” In Acts 11:28, oikoumenē is translated “all over the world” with no note. The New International Version translates oikoumenē in Luke 2:1 and Acts 11:28 as “Roman world,” but follows the same translation for Matthew 24:14 as the NASB. Here’s Young’s explanation:

Kenneth L. Barker, a spokesman for the translating committee of the International Bible Society that produced the NIV, writes: “Many—perhaps—most translators and linguists today think the greatest faithfulness and accuracy are attained when they are as true to the target or receptor language (in our case English) as they are to the source language (in this instance, the Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek of the Bible).”[2] The source language of Greek has oikoumenē not kosmos; therefore, the target language (English) should reflect the difference.

When it comes to Bible prophecy, verb tenses are important as are words used to identify the timing of prophetic events. Let’s look at several passages from the book of Revelation where many Bible translations do not translate the Greek word mellō and compare them with Young’s Concise Critical Bible Commentary:

• Revelation 1:19: “Therefore write the things which you have seen, and the things which are, and the things which will [μέλλει/are about to] take place after these things.”

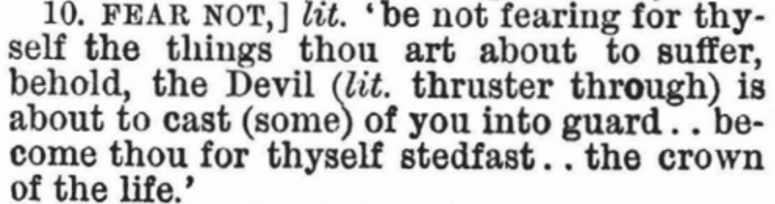

• Revelation 2:10: “Do not fear what you are about to [μέλλεις] suffer. Behold, the devil is about to [μέλλει] throw some of you into prison, so that you will be tested, and you will have tribulation for ten days.”

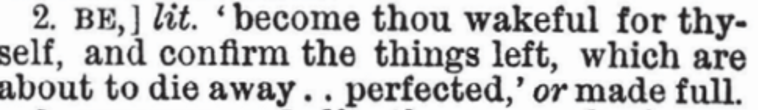

• Revelation 3:2: “Wake up, and strengthen the things that remain, which were about to [ἔμελλον] die; for I have not found your deeds completed in the sight of My God.”

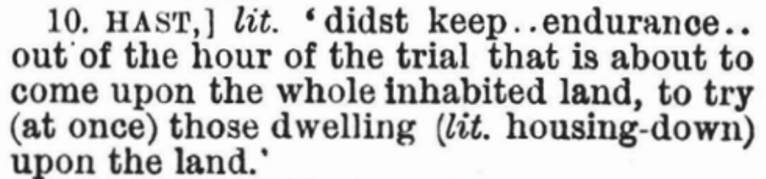

• Revelation 3:10: “Because you have kept My word of perseverance, I also will keep you from the hour of the testing, that hour which is about to [μελλούσης/being about] come upon the whole world [oikoumenē, not kosmos/Matt. 24:14; Luke 2:1], to test those who live on the earth.”

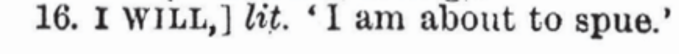

• Revelation 3:16: “‘So because you are lukewarm and neither hot nor cold, I will spit [μέλλω/I am about to spit] you out of My mouth.’”

In each case, the Greek word mellō is used. Sometimes it’s translated as “about to,” while many translations translate it as a simple future. Bible readers would never know that there is a word that is left consistently untranslated. Some claim that mellō can mean certainty without any reference to timing. I’m not sure how a translator can be certain about that. They will say the “context tells us.” But maybe it’s a person’s eschatological position that is influencing the way mellō is translated.

Why can’t mellō mean that the described event is “about to” take place with “certainty”? T. Everett Denton offers a helpful explanation:

What people do … is force mellō to have two different meanings instead of realizing that they aren’t two different meanings but two parts of one meaning. What do I “mean”? The “certainty” found in mellō is based upon its imminence, and the imminence found in mellō is based on its certainty — the two cannot and should not be separated so that we can conveniently choose which one we want in any given passage. This is why, in the McReynolds [Greek-English] interlinear, mellō is translated as “about to” in every single case, for the term expresses certainty and thus imminence or imminence and thus certainty.

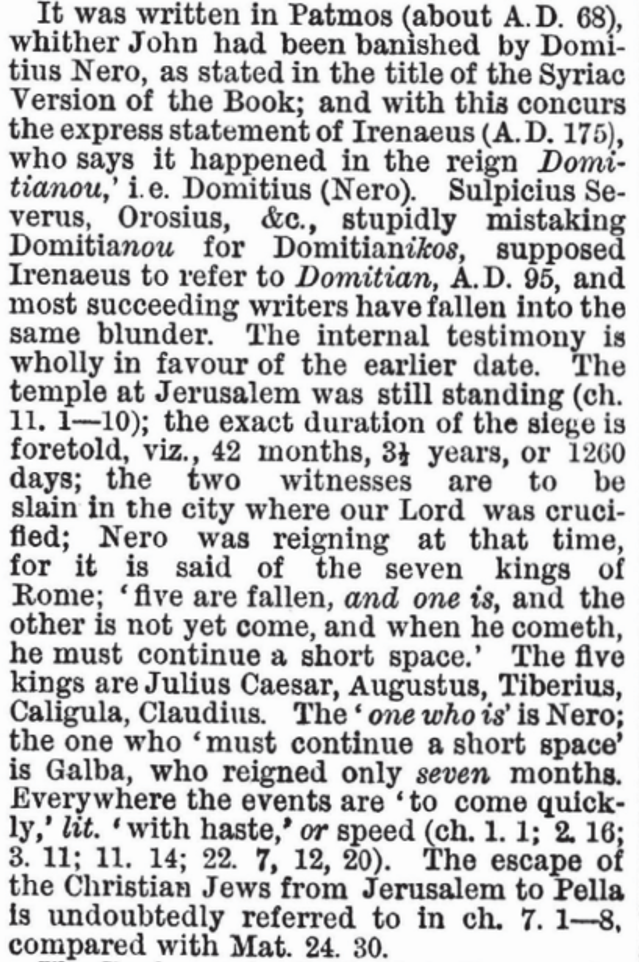

The above five verses are within the context of Revelation that states the events are “shortly to take place” (1:1) “because the time is near” (1:3). The following are some of Young’s introductory remarks on Revelation. Take note of the dating.

Young’s Concise Critical Bible Commentary on the New Testament is a great supplement teaching tool for Christians that will help with more in depth Bible study. Compare its notes with your own Bible translation as well as with online Greek-English interlinear translations. American Vision hopes to have it back from the printer sometime in September.

1599 Geneva Bible

Having your own copy of the Geneva Bible will connect you to a time when many faithful and brave Christians understood what it meant to stand and act on the Word of God no matter the cost. This completely re-typeset edition of the 1599 Geneva Bible commemorates this history.

Buy Now[1]John Snyder, Reincarnation vs. Resurrection (Chicago: Moody Press, 1984), 51. One Bible verse in isolation from the rest of the Bible should not be used to establish a doctrine. Even if the better translation is “again,” this still does not mean the Bible teaches reincarnation since there are other places that speak against it: “And inasmuch as it is appointed for men to die once and after this comes judgment, so Christ also, having been offered once to bear the sins of many, shall appear a second time for salvation without reference to sin, to those who eagerly await Him” (Heb. 9:27-28).

[2]Kenneth L. Barker, Accuracy Defined and Illustrated: An NIV Translator Answers Your Questions (1995): www.ibs.org/niv/accuracy/NIV_AccuracyDefined.pdf