While I was a student at Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, Mississippi, I was also the Assistant Manager of the bookstore. The bookstore afforded me the opportunity to learn about books, not only the authors and their content but their construction. Books from Great Britain had the best bindings. Hardback books published by the Banner of Truth Trust were beautifully designed. Older works from Zondervan and Eerdmans had solid bindings. The same was true of publications by Baker Books.

In the four years I worked in the bookstore, I began to see some changes in the bindings. There was a different look and feel about some of them. InterVarsity Press books were some of the first books to change in their construction. The hardback books looked and felt cheap. They did not open in a fan-like way.

1599 Geneva Bible

When the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Massachusetts in 1620, they brought along necessary supplies, a consuming passion for advancing the Kingdom of Christ, and their most precious cargo —William Bradford’s copy of the Geneva Bible. Also embarkation of the Pilgrims showing Bradford reading from his copy of the Geneva Bible.

Buy NowIt was then that I learned something about book construction and binding. This was before the internet. I don’t recall how I discovered how books were traditionally printed and bound, but something looked funny with the book spines. They were squarer. They looked like paperbacks. Almost all paperback books today have glued bindings with paper covers. That’s why they’re cheaper. But there was a time when even paperback books were sewn in signatures, that is, shorter printed booklets sewn together to make a book and then glued to a paper-bound cover.

I have a number of these types of paperbacks in my library. Many children’s books are still produced this way for obvious reasons. The pages won’t fall out since children are hard on books.

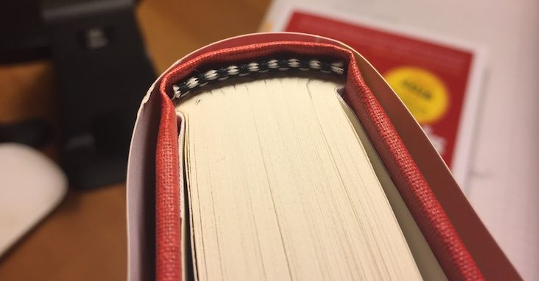

Nearly all hardback books were produced this way. Notice the rounded spine:

Over time, because of increased costs, even hardback books had glued bindings but were made to look like the traditionally sewn binding. It’s hard to tell if you don’t know what to look for.

Traditional book binding going back to Gutenberg was an art. All books were sewn in signatures. The process of printing was expensive so more than two pages (front and back) were printed at one time. Large sheets with multiple pages were printed at the same time and folded and trimmed to make small booklets that were later sewn together by hand. They were sturdy. The only thing what would break the binding was if the threading came loose or broke. I have books that are 400 years old, and they are intact. Most of the pages are still white. This is because of the paper that was used.

Prior to the mid-19th century, cotton paper was the main form of paper produced, with pulp paper replacing cotton paper as the main paper material during the 19th century. Although pulp paper was cheaper to produce, its quality and durability is significantly lower. Although pulp-paper quality improved significantly over the 20th century, cotton paper continues to be more durable, and consequently important documents are often printed on cotton paper.

The more expensive Bibles are printed in signatures and sewn together with high quality paper. These are some of the reasons some Bibles are expensive: you get what you pay for. The paper that’s used also makes a difference. It’s not cotton. Bible paper has some unique features. The paper is thin and opaque, so you don’t see the text or images from pages that are back-to-back. This is a hard balance to achieve since the thinner the paper, the more it is susceptible to bleed-through.

Some Bibles, to cut costs, do not manufacture books with sewn signatures. Unless you know what to look for, it’s hard to tell. That’s why I put this short video together to explain the process. The 1599 Geneva Bible we offer is sewn in signatures and printed on paper that is easy to read. You can order the Geneva Bible here.