Many people get bent out of shape when they see ‘Xmas’ or ‘X-Mas.’ (Don’t get me started on “ ‘Christmas’ Trees”). Critics think it’s a way of removing Jesus Christ from Christmas. Removing Christ from Christmas happens in many direct ways, but X-Mas is not one of them. “Every year you see the signs and the bumper stickers saying, ‘Put Christ back into Christmas’ as a response to this substitution of the letter X for the name of Christ.” Nothing could be further from the truth.

Part of the problem is that most people have little historical background on the subject and a general ignorance of classical languages. “Christ” is a Greek word for the Hebrew word “anointed one” or “Messiah,” as in Handel’s “Messiah.”

The Greek word for Christ is Χριστος (Kristos). The Greek alphabet does not have the letters “c” or “h.” You will find a “k” (kappa) and an “h” sound that looks like a single opening quotation mark that appears like this before a Greek word ‘. It’s called a “rough breathing mark.” It only appears at the beginning of words. The Greek word for “day,” ἡμέρα (heméra), is an example.

Thinking Straight in a Crooked World

The nursery rhyme "There Was a Crooked Man" is an appropriate description of how sin affects us and our world. We live in a crooked world of ideas evaluated by crooked people. Left to our crooked nature, we can never fully understand what God has planned for us and His world. God has not left us without a corrective solution. He has given us a reliable reference point in the Bible so we can identify the crookedness and straighten it. Gary DeMar shows the power of biblical thinking and the desperate need for it in the church today. Thinking Straight in a Crooked World is designed to identify the bends in the road of ideas and repair them with biblical, straight thinking.

Buy NowNotice that the Greek word Χριστος begins with what looks like an X, the 24th letter of the English alphabet, but it’s actually the Greek letter chi = Χ.

This short lesson would be a great way to introduce your children to biblical Greek. See my article “How to Introduce Yourself and Your Children to Biblical Greek.”

The late R.C. Sproul (1939-2017) wrote that “the idea of X as an abbreviation for the name of Christ came into use in our culture with no intent to show any disrespect for Jesus.” Using a single letter to represent a title or name is not unusual. For example, the “R. C.” in R. C. Sproul stands for Robert Charles and is not meant to demean the man.

Most Christians are familiar with the use of the symbol of the fish to represent Jesus Christ. The Greek word for fish in Greek is iχθύς (lower case letters) and ΊΧΘΥΣ (upper case letters). Each letter represents a Greek word that in abbreviated form describes the redemptive and relational work of Jesus: Ίησοῦς Χριστός Θεοῦ Υἱός Σωτήρ: (’Iēsous Christos Theou Yios Sōtēr) = “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior” or “Jesus Christ, God, Son, Savior.”

“The early Christians would take the first letter of each of those words and put those letters together to spell the Greek word for fish. That’s how the symbol of the fish became the universal symbol of Christendom,” Sproul writes.

Consider the use of X and P (the r sound in Greek) = Chi Rho. The Χ (Chi), as we’ve seen, is an abbreviation for Christ representing the first letter in the word Χριστός, and the letter “P” (Rho) represents the second letter in upper case form. What looks like a “P” to us is the Greek letter for “R.”

The Chi-Rho is common in Christian art and worship. In many of the examples, you will also find the use of A and W, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, Alpha and Omega (Ἄλφα καὶ τὸ Ὦ: Rev. 1:8; 21:6; 22:13; Isa. 41:4), also descriptive of Jesus, and found to the left and right of the XP below:

The following is from “A Word in Edgewise” by David Capes:

“Earliest versions of writing Christmas as ‘Xmas’ in English go back to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (about 1100). This predates the rise of secularism by over 600 years. The Oxford English Dictionary cites the use of ‘X’- for ‘Christ’ as early as 1485. In one manuscript (1551) Christmas is written as ‘X’temmas.’ English writers from Lord Byron (1811) to Samuel Coleridge (1801) to Lewis Carroll (1864) used the spelling we are familiar with today, Xmas.’

“The origin of ‘Xmas’ does not lie in secularists who are trying to take Christ out of Christmas, but in ancient scribal practices adopted to safeguard the divine name and signal respect for it. . . . No doubt some people today use the abbreviated form to disregard the Christian focus of the holy-day, but the background tells a different story, a story of faithful men and women showing the deep respect they have for Jesus at this time of year.”

Do not be alarmed or disgruntled when you see Xmas. If the topic arises in a discussion, do a brief “Did you know….”

Of course, for those who believe celebrating the birth of Jesus is a pagan ritual, none of the above counts. It’s important to note that the celebration of the birth of the Messiah has been corrupted and transformed into a gift-giving practice commercialized around a mythical figure named “Santa Claus” or St. Nick. Like the meaning of X-Mas, that’s some fascinating history to delve into.

Santa Claus is often mistakenly associated with pagan figures; he is, in fact, based on the historical figure of Saint Nicholas, a 4th-century Greek Christian bishop from Myra, located in modern-day Turkey. Known for his generosity and kindness. Saint Nicholas became renowned for his secret gift-giving, most famously helping three impoverished sisters by providing dowries so they would not be forced into prostitution. This act of charity led to his veneration as the patron saint of children and the inspiration for gift-giving traditions. His feast day is observed on December 6th, the day of his death), and it was common practice to purchase large gifts or marry around this time every year.

The name “Santa Claus” derives from the Dutch, who first introduced the celebration of Nicholas to the American colonies in the 1700s. The Dutch tradition of Sinter Klaas, involving gift-giving on December 5th or 6th, was brought to North America by Dutch settlers in the 17th century, particularly to New Amsterdam (present-day New York City). There’s a scene in the 1947 film Miracle on 34th Street in which a Second World War refugee from Holland sees Kris Kringle at Macy’s Department Store. She does not speak English, but Kris, playing Santa Claus, sings a Christmas song with her where Santa Claus is called “Sinter Klaas,” short for Saint Nicholas.

When Miracle on 34th Street was released in June 1947, its audience knew all too well the horrors that Holland had weathered. So, when the Dutch girl’s adoptive mother explains to Santa that the girl comes from an orphanage in Rotterdam, it would have sent chills through many. The girl’s parents clearly had died in the war, and the child is emotionally scarred as a result. She has only one wish, and that’s to connect with Sinterklaas, the Dutch St. Nicholas… The girl, who seems to be about seven years old judging by the missing front teeth, lights up when Santa suddenly begins speaking to her in Dutch and she gets the confirmation she needs: He really is Sinterklaas. (Source)

Neither Edmund Gwenn nor Marlene Lydon spoke Dutch. That’s what acting is all about.

If you look at some of the ancient fresco paintings of Saint Nicholas, you’ll find he seems somewhat like the modern-day folk character version of Santa Claus. (Source) Nicholas is often associated with the legend of slapping Arius (who denied the divinity of Jesus) at the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, where the Nicene Creed was formulated to affirm the divinity of Christ. This story has become popular as a symbol of righteous anger. Contemporary records from the Council of Nicaea, including those by Eusebius of Caesarea, do not mention any such altercation. Furthermore, his name is absent from the earliest official lists of bishops who attended the council, casting doubt on his presence. Like the fictional Santa Claus, it makes for a compelling story.

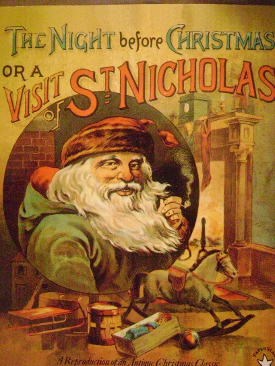

The 1823 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (commonly known as “The Night Before Christmas”) by Clement Clarke Moore further solidified the image of a jolly, rotund Santa Claus arriving on Christmas Eve in a sleigh pulled by flying reindeer.

This poem laid the foundation for the modern conception of Santa Claus, including his appearance and method of gift delivery.