All worldviews are by definition belief systems, even atheism. Since we are all limited in knowledge and restrained by our inability to be everywhere (omnipresence) and know everything (omniscience), an atheist puts forth his claim that God does not exist in terms of a faith commitment. When the late Carl Sagan wrote “The cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be,” ((Carl Sagan, Cosmos (New York: Random House, 1980), 4.)) he was making a declaration of faith. There is no way he could be assured that God does not exist based on his limited knowledge and experience and the limited knowledge and experience of others. In the first line of the next paragraph of Cosmos Sagan admits that “the size and age of the Cosmos are beyond ordinary human understanding.” ((Sagan, Cosmos, 4.)) Even so, Sagan was convinced that the material world is all that exists. He believed something to be true without having all the facts or the ability to understand what he did know. Sagan’s assertions do not conform to reality.

Everybody believes something, and even what appears to be a rejection of all beliefs is a kind of belief. We all hold something to be true. Maybe what you hold true is that nothing else is true, but that is nonetheless something you believe.

Even if you are agnostic, ((The word agnostic was coined by Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895). The word is comprised of the prefix a which means “without” or “having none” and the Greek word for “knowledge,” gnosis. An agnostic is someone who is without knowledge on a subject. A religious agnostic claims that he does not have enough knowledge to determine whether God exists. The Bible claims otherwise: “That which is known about God is evident within them; for God made it evident to them. For since the creation of the world His invisible attributes, His eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly seen, being understood through what has been made, so that they are without excuse” (Rom. 1:19–20).)) you believe that it is not possible to know things about ultimate issues like the existence of God. You believe in the justifiability of your agnosticism—your uncertainty—and you have a burden of proof to justify your unwillingness to decide. There is nowhere someone can stand where he or she has no beliefs.

If you reject Christianity, there is something else that you end up asserting by default. ((Greg Koukl, “You’ve Got to Believe Something,” The Plain Truth (January/February 1999), 39.))

Once a person rejects Christianity, he has not set himself free from the concept of faith. He has only transferred his faith to something or someone else.

Christian apologetics begins by establishing an authoritative starting point. Like Archimedes who once boasted that given the proper lever and a place to stand, he could “move the earth,” the Christian apologist seeks to base his defense on a sound foundation to move the hearts and minds of sinners to embrace the eternal hope found in the gospel of Jesus Christ. But upon what would Archimedes stand to accomplish such a feat? He couldn’t use the earth to move the earth. Archimedes needed a place to stand outside the earth, a place different from the earth he wanted to move. His lever also needed a fulcrum. This, too, had to rest on something.

Atlas had a similar problem when he was condemned by Zeus to stand eternally at the western end of the earth to hold up the sky. (In artistic renderings, Atlas is depicted as holding up the world.) But what is Atlas standing upon? And what is what he’s standing upon standing upon? What’s supporting Atlas? (You can see where this is going!)

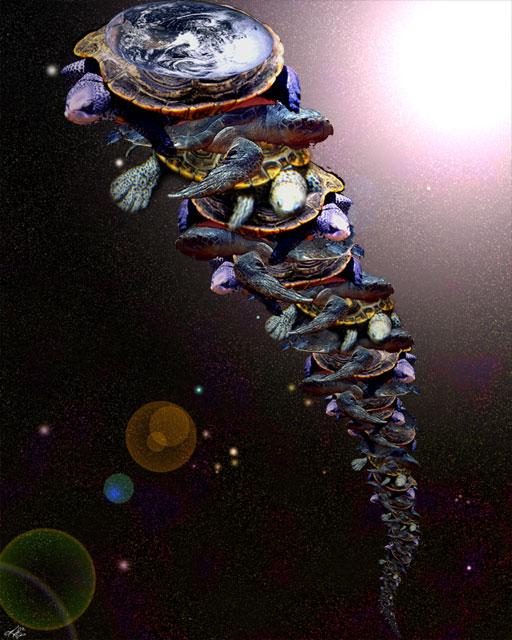

An often told story has a modern philosopher lecturing on the solar system. An old lady in the audience avers: Earth rests upon a large turtle. “What does this turtle stand on?” the speaker needles. “A far larger turtle.” As the scholar persists, his challenger retorts: “You are very clever but it is no use, young man. It’s turtles all the way down.” ((Charles W. Petit, “Life and Culture: Cosmology,” U.S. News & World Report (August 16/23, 1999), 74.))

“Turtles all the way down” is the humanist’s dilemma. Instead of turtles, it’s humans all the way down. Anyone involved in debate over any topic must deal with the issue of a sound and fixed starting point. It is fundamental. All debate will finally come to rest on a starting point. In the final analysis, the Christian’s starting point is the Word of God. When the sixteenth-century Reformer Martin Luther “was called to defend his rejection of indulgences before the church and before the emperor, Luther, alone and in peril of his life, appealed to the authority of the Word of God. ‘Here I stand,’ he said; ‘I can do no other.’” ((Gene Edward Veith, “Millennium on our Mind,” World (August 7, 1999), 27.)) There was no appeal to tradition, the expert testimony of church scholars, scientists, or even the creeds. It’s not that these aren’t helpful; they simply are not authoritative ultimate starting points.

In Matthew 7:24–27 Jesus points out that “the strength of a foundation determines the ability of a house to withstand heavy rains and strong winds. If a man builds his house on sand, it will fall; but if he builds his dwelling on solid rock, it will stand secure even in a fierce storm.” ((Richard L. Pratt, Jr., Every Thought Captive: A Study Manual for the Defense of Christian Truth (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1979), 1.)) If the foundation upon which the apologist uses to build his worldview is compromised in any way, then it will eventually collapse when challenged. Therefore, the starting point in any defense of the truthfulness of the Christian worldview is all-important. Will it be a foundation of sand or one of solid rock?