Shifts in worldviews take time even though single events seem to mark their transition period. Seemingly unrelated events and thoughts work their wizardry to produce unfathomable results. Once the shift has taken place, only a retrospective look will reveal the philosophical ebbs and flows that erode worldview landscapes.

The twentieth century began on an optimistic note but quickly lost its idealism as war engulfed the world. World War I “shattered much of Europe’s already fading optimism, and the advent of Nazis and fascists shook men’s confidence in their present and their past.” ((Gary North, Unholy Spirits: Occultism and New Age Humanism (Tyler, TX: Dominion Press, 1986), 22.))

Despite a bloody world war, belief in evolutionary progress had not lost its luster. In 1920, the English novelist H.G. Wells wrote The Outline of History, described as “a song of evolutionary idealism, faith in progress, and complete optimism.” ((Herbert Schlossberg, Idols for Destruction (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, [1983] 1993), 2.)) Before too long, Wells began to lose hope in what he believed would be the inevitabilities of evolutionary advancement and social enrichment.

By 1933, when he published The Shape of Things to Come, he could see no better way to overcome the stubbornness and selfishness between people and nations than a desperate action by intellectual idealists to seize control of the world by force and establish their vision with a universal compulsory educational program. ((Schlossberg, Idols for Destruction, 2.))

An elite class of social engineers would be needed to force the “good society” on people whether they wanted it or not. “Finally, shortly before his death, [Wells] wrote an aptly‑titled book, The Mind at the End of Its Tether (1945) in which he concluded that ‘there is no way out, or around, or through the impasse. It is the end.’” ((Schlossberg, Idols for Destruction, 2.))

The outlook in America was different. A form of secular optimism prevailed after World War II that even a police action in Korea in the 1950s could not dampen. America had never known defeat in war, and her countryside had not been ravaged by incendiary bombs or nuclear fallout. She was on a roll.

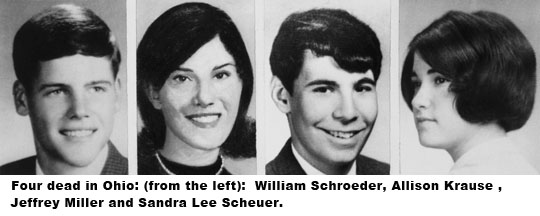

The post‑war optimism continued with the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy in 1960 and dreams of Camelot. “The phenomenon we call ‘the Sixties’ did not begin at 12.01 A.M. on January 1, 1960. It is not a chronological entity so much as a cultural or mythic one. Even if we identify the myth with the decade, it would be more accurate to say that it began on November 8, 1960, with the election of John F. Kennedy, and ended May 4, 1970, on the campus of Kent State” when National Guardsmen killed four students as a crowd gathered to protest escalation of United States military policy in Vietnam. ((Annie Gottlieb, Do You Believe in Magic?: The Second Coming of the 60’s Generation (New York: Random House/Times Books, 1987), 17).))

The students were not only unarmed; most didn’t realize that the guards’ rifles held live ammunition. Four students were killed: Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandra Scheuer and William Schroeder. Nine others were injured. After 50 years, we still don’t know why the guard turned and fired.

*****

Looking back, 50 years later, we can also see clear but less tangible effects. Along with cultural touchstones like the Manson family murders and the concert at Altamont, Kent State marked the symbolic end of the 1960s, stretching from the optimism of John F. Kennedy’s inauguration through the March on Washington to the long hot summers of riots, assassinations and radical activism. If, as the sociologist Todd Gitlin noted, the decade was marked by both hope and rage, then the events of May 4 brought the sober recognition that neither could overcome the will of a militaristic state and a conservative political backlash. (New York Times)

Modernism was running full throttle in the early 1960s with its great scientific advances — man was about to conquer the heavens and put a man on the moon — and official judicial statements of atheism with prayer and Bible reading removed from America’s public schools. The theistic house cleaning was now nearly complete. Since 1859, the year that Darwin’s Origin of Species was published, modern man had been trying to rid the universe of God and the supernatural. America was about to show the world what man could do without God.

On November 22, 1963, gunfire put an end to the euphoria. As one child of the 1960s put it, “When Kennedy was killed is when America changed.” ((Quoted in Gottlieb, Do You Believe in Magic?, 17.)) As if overnight, everything seemed to change. “Tennessee‑born photographer Jim Smith, who describes his experience of the Sixties as ‘having my world view torn apart with nothing to replace it,’ says that ‘the Kennedy assassination really was the trigger.’” ((Quoted in Gottlieb, Do You Believe in Magic?, 18.)) The following social chaos was hardly encouraging to an idealistic generation:

Lyndon Johnson’s skillfully and ruthlessly imposed legislative substance — the final culmination of the old Progressive optimism — soon turned to dust in the mouths of his followers. The Vietnam war, race riots, and the deficit‑induced price inflation broke the spirit of the age. Johnson could not be re‑elected in 1968, just four years after he was elected President. ((North, Unholy Spirits, 23.))

From visions of Camelot to chants of “Hey! Hey! LBJ! How many kids didja kill today?” America was abandoning what little faith it had in the secular religion of modernism. As if tens of thousands of dead young men were not enough to destroy the worldview of modernism, the murder of two cultural icons confirmed the disintegration of society. “With the assassinations of King and Robert Kennedy, we lost our last hope of combating racism or ending the war through the System, and the System lost our consent.” ((Gottlieb, Do You Believe in Magic?, 47.))

A crisis of secular faith had emerged. The new generation questioned the orthodoxy of rational neutrality. The guardians of modernism had sent young men and women to the rice paddies of Vietnam, and more than 58,000 of their names grace the Vietnam War Memorial in our nation’s capital. A break with the past was unavoidable. People were calling for “revolution.” They “wanted apocalypse, Utopia,” ((Quoted in Gottlieb, Do You Believe in Magic?, 18.)) a world transformed. Transformed by what to what? That was the question.

Drugs, sexual experimentation, Eastern philosophy, and the occult were all viable options. The counterculture of the 1960s wanted something more than the impersonalism offered by a sterile rationalism. In fact, the best and the brightest of the rationalists had sent America’s youth to Southeast Asia to die. ((David Halberstam, The Best and the Brightest (New York: Random House, 1972).)) For the first time in her history, America had lost a war. It is no wonder that George Will called the 1960s “the most dangerous decade in America’s life as a nation.” ((George Will, “1968: Memories That Dim and Differ,” The Washington Post (January 14, 1988), A27.))

Postmodernism is the logical outworking of modernism. Stephen Connor says that the “concept of postmodernism cannot be said to have crystallized until about the mid‑1970’s….” ((Stephen Connor, Postmodernist Culture: An Introduction to Theories of the Contemporary (Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell, 1989), 6. The fall of communism in 1989 drove the nail into the coffin of modernism.)) Modernism had received some strong criticism, and it was becoming more tenable to assert that the postmodern had come to stay, but it took some time before scholarship really jumped on the bandwagon. ((It is important to distinguish between postmodern and postmodernism. Postmodern refers to a period of time, whereas postmodernism refers to a distinct ideology. As Veith points out, “If the modern era is over, we are all postmodern, even though we reject the tenets of postmodern_ism_” (Gene Edward Veith, Postmodern Times: A Christian Guide to Contemporary Thought and Culture (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 1994), 42).)) Events, violent events, forced the hands of the academic community.

If May 4, 1970, was the day that the war between the generations and classes of white America became a war in earnest, in retrospect it was also the day that war began to end. It was as if the rising tensions had needed to climax in the taking of life. After the strikes in the wake of Kent, the energy of confrontation began to ebb. ((Gottlieb, Do You Believe in Magic?, 138.))

But little was resolved. The four young people who were killed at Kent State University by National Guardsmen, through no will of their own, put an end to a misguided revolution. The worldview of modernism was buried with them. The campuses in the 1970s, and even through the 1980s, remained eerily quiet. The silence, however, was not a sign of inaction. A new worldview was being developed without fanfare — a quiet revolution impacting our nation today.

Saul Alinsky, the architect of today’s leftist politics, special interest groups, and the deep State, boldly outlined the needed tactics in his silent revolution primer Rules For Radicals that would establish the New World Order’s marching orders:

Do one of three things. One, go find a wailing wall and feel sorry for yourselves. Two, go psycho and start bombing — but this will only swing people to the right. Three, learn a lesson. Go home, organize, build power and at the next convention, you be the delegates.

Coupled with the earlier directives of Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937) of a “‘long march through the institutions’—the arts, cinema, theater, schools, colleges, seminaries, newspapers, magazines, and the new electronic medium [of the time], radio,” ((Patrick J. Buchanan, Death of the West: How Dying Populations and Immigrant Invasions Imperil Our Country and Civilization (New York: St. Martin’s Press/Thomas Dunne Books, 2001), 77.)) they’ve nearly succeeded.